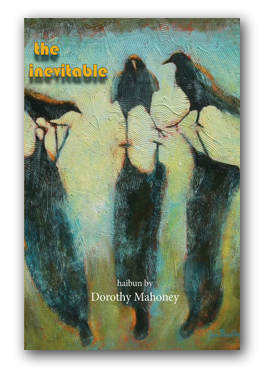

Book Review: The Inevitable

By Dorothy Mahoney

Published by Red Moon Press

2022, Paperback, 116 pages

ISBN 978-1-958408-05-6

$20.00 US

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Rich Youmans

The daily news has always been weighted toward the darker aspects of existence, as if the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse occasionally moonlighted as editors. In her new book, The Inevitable, Dorothy Mahoney uses some of those grim stories—from environmental disasters to human atrocities to the bizarre tales often found in supermarket tabloids (“Road Repair Crew Accidentally Buries Drunken Man Alive”)—as inspiration for an ambitious collection of haibun that raises questions about the nature of reality.

In the acknowledgments, Mahoney says that the haibun began as “drabbles”—100-word flash fictions—inspired by actual news events and created on the self-publishing platform Drablr.com. She also refers to the book as an “experimental novel”: rather than just collecting and presenting the best of her bad-news haibun, she sandwiches them between the opening and closing of a single piece of flash fiction titled “The Inevitable.” In so doing, she creates a whole new context in which to view the collection.

When I first read the title, I immediately thought of death and taxes. The flash story, however, begins with what I assume is another explanation of the book’s title: “It is a trick. You know the kind. You choose three cards which return to the deck, cut the cards three times, and the dealer reveals which cards were chosen, one at a time as he reshuffles them.” The story then recounts the narrator’s chance meeting, during an airplane flight, with a man who is a magician—or rather, an illusionist, his preferred term. Pulling out a deck of cards, he offers to perform the title trick. That begins a conversation that touches on the basics of the magic trade (e.g., the cost of props) and famous tricks, which leads into the narrator’s own pondering: What happens to rabbits when they “disappear” into black top hats? Are things ever what they seem?

The piece stops (pauses, actually) with the sentence “The inevitable happens.” That catapults the reader into the series of haibun. They start mildly, if ominously: food being overrun by ants, bees amassing on a city street. Soon the scenarios get darker: a sperm whale beaches and dies, the memory of a Hiroshima survivor is retold, a wildfire rages uncontrolled. And weirder: a father’s ashes are stolen by teenage burglars. There are 51 haibun total, all of which take the common format of prose followed by one haiku. After the last haibun, we return to the conclusion of that opening flash, which serves as something of a coda: the plane lands; the narrator disembarks, she finds a waiting friend—and also discovers, in her pocket, three playing cards the illusionist has somehow placed there. Presumably, they are the three cards she chose.

What to make of all this ultimately depends on the reader. For my part, I assume it means something that there are 52 pieces (the haibun plus “The Inevitable”), the same number as playing cards in a deck. Are the individual stories no more than cards themselves, fates that, as in an illusionist’s trick, follow us and will appear when we least expect it? Is everything pre-determined or, to put it another way, inevitable?

Wow. Another reader, of course, might look at this and tell me to stay away from the mushrooms. Still, it’s a fascinating rabbit hole into which readers could disappear (things are never what they seem), and I have to applaud Mahoney for creating a framework that elevates the collection into the realm of the novel and allows all the parts to cohere into a greater whole.

But in the end, this is still a collection made up primarily of haibun, and any evaluation has to take into account whether they work as such. I admire anyone who can create a narrative in 100 words, and Mahoney does it well. (In a number of the haibun, the prose actually clocks in at under 100 words.) As can be expected, the narratives are allusive, with plenty of blank spaces for the reader to fill in. Here’s one:

‘disappeared’

You can follow the vultures, circling, and you can walk the roadside ditches, search where the weeds are thickest. Sometimes, someone will whisper, there are places in the hills where rocks are rearranged.

You can lean a shovel against the house, ready.

Sometimes you can imagine waking up and he’s back. His shoes have moved, his chair is pulled back, his bed unmade. But you are only waking up. You want to sense his presence. It has been too long for worry now. If they march to your door, you will act sincere, say he is gone to the city.

on the back stoop

a pair of work boots

missing tongues

I’m not sure what news item inspired this story; it could have been of a missing husband who left one morning and was never heard from again (which the haiku nicely picks up with the shoes’ “missing tongues”). But while the title ties in to the book’s “magical” theme, it also reminds me of the “disappeared” during El Salvador’s bloody civil war in the 1980s, when those suspected of being “enemies of the state” suddenly vanished. That last context makes the haiku all the more chilling; a 1981 Amnesty International report noted that the Salvadoran regime’s military and security units often tortured and mutilated the country’s civilians (see Carolyn Forché’s “The General”). Who is the “they” marching to the door? Detectives? State authorities? This is a haunting piece that works on many levels and shows Mahoney’s deftness as a writer.

There were a few haibun that provided enough details for me to search online and find what must have been the inspiring news story. In all cases I liked how Mahoney molded the tales into something more than just a retelling. “Contents” draws from a horrid episode in which a couple tortured the woman’s three-year-old daughter to death, then placed her body in a suitcase in the freezer. Mahoney takes the gruesome tale and, in some ways, makes it more terrifying by ignoring the gory details and emphasizing the mystery:

What is in the freezer: a package of weightless hot dog buns, dried out fish sticks, a suitcase. What’s in the suitcase? A could-be answer for a customs officer, a pair of shoes, socks, missing underwear, a wrinkled dress, a hairbrush. An answer for a curious child on the subway; be glad it’s not you. An answer for a stranger waiting for the next stop: a question at our feet, which squeezes us tight and even tighter. A suitcase can be dropped into a river or a garbage bin, burned in a vacant lot, stored in a freezer.

luggage tag

none of the blanks

filled in

In a couple of cases, several haibun (usually three—there’s that number again) work together to form a loose sequence. For instance, the haibun “Crossing” introduces us to a woman who appears to be leaving her husband or lover surreptitiously (“And then there was nothing left to say anymore. The silence widened like a river spread by a spring runoff, cold and bitter”). That’s followed first by a piece that focuses on a man who’s under a restraining order after tormenting his ex-wife and her new boyfriend, and then by one in which a father encourages his children to pretend they’re all somewhere else:

frozen

Let’s pretend. He holds their small hands. Let’s make believe this is a castle. We are not who we are. Outside the real snow has covered the real hotel, has covered the real roads, cars, covered where we come from. Here we are. Let’s pretend you are the princess. You be the reindeer and you be the snowman. Let’s pretend your favourite movie.

“Let it go”

repeating the chorus

loud, louder

I have no idea what news story inspired this haibun, either (other than one perhaps announcing the debut of the Disney movie) and it’s a little bare on its own, but I find it especially poignant coming after the previous two haibun. However, it also raises the one critique I had while reading the book: I wish some of the haiku had been honed a bit further. When reading haibun, I’ve always looked to the haiku to present me with something that couldn’t be rewritten into the prose, at least not to equal effect. In the case of “Frozen,” I appreciate what the haiku is trying to do, but for me the reading experience would have been the same (if not better) if Mahoney had written it simply as short prose, with “Let It Go” as the title and a new last sentence, “Repeat the chorus loud, louder.” Maybe it’s because these haibun started as “drabbles” and the haiku were retrofitted—according to Mahoney’s bio, they evolved through a Buson challenge in which she wrote 10 haiku a day for 100 days—but there were a few such instances where the haiku could have been honed. In “Miracle,” for example, a survivor of a building collapse describes both the elation of those who find him alive and the disorientation of his own life-changing mutilation. It ends with this haiku: “hearing his voice/but not/the words he says.” Again, I appreciate the intent of the poem—bringing in the muffled calls for help through rubble, the rescuers reveling in the moment of discovery without seeing what survival really means—but it’s more of a phrase than a haiku. Mahoney is good enough that I can’t help but think a few more drafts would have produced a stronger poem.

That critique, however, shouldn’t undercut the fact that The Inevitable is an impressive achievement. Every writer of haibun should take note of this “experimental novel”: it not only contains some excellent individual pieces, but also explores another way in which haibun can expand. Quite the trick.

About the Reviewer

Rich Youmans lives on Cape Cod with his wife, Alice. His books include All the Windows Lit (Snapshot Press, 2017) and Head-On (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2018).

Thank you for your close reading and your thorough review, Rich. I especially appreciate your comments on the avalanche and the earthquake haiku. Music or the sound of a human voice can take the form of salvation when all else is lost, as in “key”.

Your suggestion that the haiku should contain what can’t be rewritten into the prose is

a litmus test for future writing. Sincerely, Dorothy