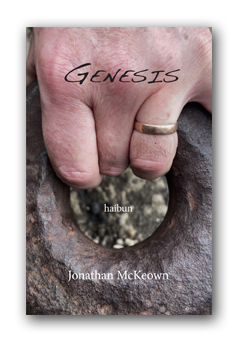

Book Review: Genesis

By Jonathan McKeown

Published by Red Moon Press

2022, paperback, 224 pages

ISBN: 978-1-947271-91-3

$20.00 US

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Kristen Lindquist

Like its biblical namesake, Jonathan McKeown’s Genesis is a big book, the kind of book one commits to for the long haul rather than reading straight through in one or two sittings. This feels like a life’s work in more than one sense: it contains many noteworthy haibun (and stand-alone haiku) that have been seen in journals over the past several years, and it covers a lot of territory, from childhood to the present, with the gravitas of a well-crafted memoir. The roughly chronological collection is not broken up into sections, so the narrative flow is unimpeded. It’s worth taking in these 90 haibun slowly, because there’s a lot going on here.

McKeown himself describes his poems as “sketchy,” as “track notes of my efforts at attending, at listening, at noticing, at trying to understand the language of ambiguity, of paradox, of that voice at once strange and familiar like the sound of the evening breeze, like wind through mountain pines or river bank casurinas.” But while the prose style of his haibun is often discursive and conversational, with lots of dashes and ellipses, there’s nothing sketchy about their content. In “Windhover” someone explains why they didn’t resort to suicide:

No matter how hopeless my life seemed . . . and though I couldn’t believe, I couldn’t actually once-and-for-all deny—the possibility . . . —of hope, I suppose; of a good beyond that of my own monotonous desire . . . Do you know what I mean?—If possibility existed, tomorrow, next year, who knows . . .In a certain respect it’s easy to deny, but somehow . . .

dead wood

the ministry

of wind

One feels the emotion in those pauses, hears a real voice. (Interestingly, the original version of this haibun, published in A Hundred Gourds, was titled “Genesis.”)

By titling his collection Genesis, McKeown signals that these poems are about where he comes from. They are his origin stories, featuring childhood memories, dreams, family, relationships, the landscape of Australia, books he’s read, the state of the environment: what has moved him and made him who he is. The creation of this kind of poem thus engenders fresh consideration of one’s life, whether at the level of its smallest details—a pocketknife, an opossum, a favorite tree—or on the larger scale of being human. Or both, as in one of the shortest haibun in the book:

Kingdom of the Heavens

In a remote area of the Buddewang Ranges I stop for a drink of water and notice a small wildflower quivering in the heath. With nothing demanding my attention I give it to the little flower and wonder . . . out here, has anyone ever noticed its existence.

above the flicker

of fire-light in the trees

countless twinkling stars

McKeown is a thoughtful, well-read man. From him we learn about Darwin, Nabokov, Australian aboriginal art, the Earth’s shifting magnetic fields, music. His pieces are almost always top-loaded with epigraphs, including many from the book of Genesis. (Others from Nietzsche, Rilke, Aldo Leopold, Lorca, Thomas Merton, et al., bring in some literary diversity—although Sappho might be the only woman quoted.) But the biblical epigraphs don’t burden his poems with any particular religious weight. The verses are as elusive as they are allusive, with each one becoming yet another colorful strand running through the fabric of the haibun.

Take “No Man Is an Island,” for example:

No Man Is an Island

. . . but for the human . . .

—Genesis 2:20This morning I disturbed a grey heron’s reverie, walking out along the broken vertebrae of jagged rocks to Barlings Island. It watched a while, how far I’d come. Too close, evidently. Uplifting itself, banking into the breeze, it wafted off around the head, needing a certain distance to be at ease. Heron-like, I stood a while, beneath ashes of a Lenten moon . . . A pair of pied cormorant were fishing around the rocks, alternate heads, appearing, disappearing . . .

tyre tracks in the sand

a lobster shell, remains

of a fire

The cryptic scrap of an epigraph refers to the situation in Eden after Adam named the animals but before Eve was created: all creatures had mates at that point except for him. At the simplest level, the epigraph telegraphs themes of isolation and disconnection, similar to the way a one-word kigo can elicit a larger shared cultural/natural experience. In this way, McKeown enlists the epigraph as a fourth crucial element of his haibun, almost on par with the title (his titles are also often allusive, as here), prose, and haiku. It’s a masterful way to deepen the layers of meaning inherent in the form.

As another good example, in the haibun “Mycelium,” the first of two epigraphs is a passage from Genesis 3:20: “…she was the mother of all that lives.” In the Bible, this is Eve, the mother of humanity. But beyond the literal Eve, this epigraph ties more closely to a discussion of the underground mycelial network as foundation for the living landscape—fungi as Mother Nature. Additionally, it connects with the mother that appears in the closing haiku:

mushroom picking

something about his mother

he never knew

McKeown often uses additional epigraphs to introduce even more layers to a poem, which can feel like overload at times. There’s already a lot here, and sometimes too many strands simply snarl.

The stand-alone haiku between the haibun offer much-needed white space, but are easy to overlook in such a long book. This is unfortunate, because they have been well chosen to resonate with the adjacent haibun. Facing “Circles,” a piece about a dive-bombing goshawk defending its nest, we find air raids begin / tremors in the scroll / of the Zantedeschia. The first piece in the book, “A Tree,” focuses in part on childhood memories and ends on a lovely note with endless sky / my first thought / of eternity. The two facing stand-alone haiku sustain the sky image: gas guns punctuating the crowless sky and rural blue a small plane cuts its engine.

Interestingly, some of the stand-alone haiku show up elsewhere in the book within haibun. For instance, all four of the haiku in “‘This Lolita'” appeared previously in the book, two in a very different format and one in another haibun. This practice sets up echoes that repeat throughout the book, as well as offering an intriguing glimpse into McKeown’s creative process.

As an example, the final haiku of “This Lolita” follows his wife’s vehement response of denial to the speaker’s question about whether Humbert really loved Lolita: streetlight my undoing her negligee of venetian shadow. Here, the haiku takes on an almost predatory tone. This same haiku shared earlier in the book as a vertically structured stand-alone takes on a more slow and sexy vibe as it faces the dream narratives of the haibun “To Be or Not To Be”:

streetlight

my undoing

her negligee

of venetian

shadows

As another revealing example, in “Bar Island” the second paragraph of text concludes:

Did you read the headstones? Some, she says. What do you think it means?—the young and the strong who cherished noble longings for the strife. Maybe the War, she says. Although he died in 1887 . . . Did you notice all the children’s graves?

winter sunlight creeping across cracked marble camellias

In “This Lolita,” this same haiku follows an opening scene in which the speaker, in that “spellbound state of mind” after having just finished a good book, gradually becomes aware that his wife is “quietly folding washing at the end of our bed.” The haiku works differently in each haibun, but with equal resonance.

There’s so much to linger over and enjoy in this book. The lyrically beautiful “Peaches and Cream”—about milking songs and a happy childhood memory—is a favorite:

Peaches and Cream

Being begins with well-being.

—Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space. . . cursed shall you be by the soil that gaped with its mouth . . .

—Genesis 4:11The milking songs in Carmichael’s Carmina Gadelica take me back to my childhood, to our little farm at Silverdale, and the two milking cows my mother named Buttercup and Daisy. My brother and I used to call them up in the mornings. We’d sometimes watch Dad wash their pink freckled udders and teats with a soft muslin cloth that he’d rinse and wring with his hands in a bucket of warm water before he set to milking. I remember the rhythmic sound the milk would make squirting into the bucket.

dusk deep in the valley of a cow’s falsetto

Number 99, titled simply ‘Milking song’, I find especially moving and consult the notes at the end. Carmichael says these songs were sung to induce the cows to give their milk, that some became so accustomed to a milkmaid’s lilt that without it they’d refuse. Our science and technologies have come a long way, but reading things like this one can’t help feeling something also has been lost . . . The delight I felt as a child, sitting in the shade of the barn on a hot summer afternoon with a bucket of over-ripe peaches that Mum had collected from under the trees. The sweetness of her voice in her songs as she pared away bruised bits from the stones is so mingled now in memory as the aroma of ripe peaches with those juicy bits of flesh she handed each of us in turn.

still life

a bowl of fruit

with little stickers

Other favorites include “The Monk’s Rosary,” a piece about an old girlfriend that includes an actual mix tape playlist, and “Ubirr,” a consideration of aboriginal art. “Lockdown Mullet” introduces some pandemic levity. Through haibun, we follow the poet/speaker as he copes with various life events—growing up, aging parents, divorce, children, a remarriage—as he remembers, as he thinks. We become engaged in a life narrative that’s both internal and external.

One might argue that with so much going on, two, or even three, smaller books might have done more justice to the individual haibun, or at least have been a little easier on the reader. But there’s an epic quality about this book that one grows to appreciate. It rewards well those willing to slow down and take time to think.

About the Reviewer

Kristen Lindquist is a poet, writer, and naturalist in Camden, Maine. She has published several collections of poetry, most recently It Always Comes Back (Snapshot Press, 2021), and maintains a daily haiku blog at kristenlindquist.com/blog.

Thank you for reading my book so thoughtfully Kristen. It is gratifying to hear rumours of it’s independent life. Warmly, Jonathan

It was such a pleasure, Jonathan! I think reading and re-reading it helped get me through a bout of Covid with my brain intact! I look forward to reading more of your work in the future… Kristen