Book Review:

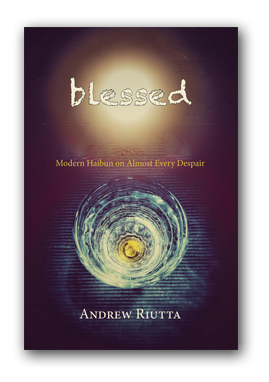

Blessed: Modern Haibun on Almost Every Despair

By Andrew Riutta

Published by Red Moon Press

2022, paperback, 164 pages

ISBN 978-1-958408-07-0

$20.00 US

Ordering Information

Reviewed by John Zheng

Despair and hope coexist like twins in Andrew Riutta’s new book, Blessed: Modern Haibun on Almost Every Despair. The book’s 78 poems delineate human relationships, share personal reminiscences and observations, and reflect on the lives of friends and relatives who have suffered, laughed, loved, and, most of all, endured. While the reasons for despair may be many—”More war. More rape. More disease. More starvation. More grinding teeth, more dirt-caked bones,” as Riutta lists in the book’s last haibun, “Notes on Almost Every Despair”—Riutta’s haibun offer both relief and enlightenment, in language that’s imagistic, colloquial, and even at times funny.

Hope sounds more like a wish in some of his haibun. Take “Life Out of Balance,” which shows two sorts of despair. The speaker is smoking in a camper at four o’clock in the morning; his despair means simply an out-of-balance night short of sleep. It’s set in contrast to the deeper despair of an old Native American woman, whom the speaker “can’t stop thinking about.” Her despair is much larger and deserves not only our sensitivity to her feelings but also empathy for her people’s sufferings. Riutta chooses a fact—a house without indoor plumbing—to suggest her daily life which has been out of balance, yet she never gives up. Instead, she keeps her hope by hanging an eagle feather on “a crucifix on her kitchen wall” as a symbol of hope. She says that “when the Lord comes back, she will give him that feather and a bowl of corn soup and maybe then Mother Earth’s tumors will go back to being butterflies and she and her people can be people again.” The concluding haiku seems to indicate a blessing:

instant coffee—

I swallow the crack

of dawn

It is poignant that this woman—who has nothing blessed in her current reality, which she tolerates without basic modern needs—wishes for nothing but her people’s better and more humane treatment, and for “Mother Earth’s tumors” to metamorphose into butterflies. On the webpage of the literary journal that first published this poem, MacQueen’s Quinterly, a note by Riutta deserves a read to better understand his creative push:

I met Hazel at a Native American youth camp, where I was a counselor. She was our cook. We’d sip coffee in the mornings and chat while she prepared breakfast. A dear friend she eventually became. I believe she may have had indoor plumbing the last few years of her life but I’m not positive. We lost touch. She had a heart that could soften the weight of any conflict. Dearly loved her.

Many of those whom Riutta has dearly loved are represented in Blessed; one-third of the haibun are dedicated to friends and relatives. “Irene,” for example, is written for Irene Riutta, the poet’s grandmother, who brought with her “the recipe for making a home” after emigrating to her new country. The freshness of this haibun is that the recipe highlights things concerning religion, survival, hardship, and family; its dozen ingredients include stacked Bibles, a can of lard, “a stiff finger to break the soil,” a faithful husband, and “the word for ‘hope’ in Finnish.” As shown especially by this last item, this poem too offers glimmers of hope rather than despair. The haibun ends with one last ingredient that pulls everything together, and the recognition that even though life is “an endless road,” much can still be made of it. (It may even hold a few surprises, as the reference to the “Sing a Song of Sixpence” nursery rhyme attests).

Finally, a Formica table to roll it all out. To flatten the dimensions . . . to bring heaven closer to earth.

endless road—

the sky curves

into blackbirds

While most of the dedication poems mention the person’s name at the bottom of a page, the epistolary haibun “Dear John” addresses a dead friend directly, shortening the distance between the two. The speaker apostrophizes his thoughts and concerns about his friend’s whereabouts, with a wish to know whether in heaven the clouds “come casual and soft, like lilacs,” whether it has rivers or streams “perfect for you casting and delivery,” whether he still has the sharp pain in his arms from falling off the roof, or floaters in his eyes. (“Were they, in truth, just the ghosts you couldn’t avoid, especially your mother?”) Riutta avoids falling into the sad state of profound memory. Instead, through twelve questions in four short paragraphs, he presents a vivid picture of his friend. The prose ends in a lighthearted way: “And does the scent of that young bartender’s perfume yet float for you? Still make you want to roll around in the dirt like a dog?” That’s followed by a haiku that captures the poet’s sense of loss:

Hunter’s Moon—

the bone-chilling sound

of an empty tin cup

As shown in the preceding examples, Riutta writes well and employs fresh images to bring readers into the moment. In “Lupus,” the description of a young person after dialysis immediately conveys a sympathetic tone through the two visual comparisons:

After dialysis, she looks like a flower that’s been pressed too long inside the pages of a book. Or a deer gaunt from winter, afraid of the wind.

He also has a keen eye for finding something new in the commonplace. Take, for example, “Spring Sunshine.” The title image may embody the upbringing of life, but here it also carries thoughts of death:

Jesus. I guess I never really noticed it before, but each drip of melted snow falling off the eaves practically digs its own grave in the thawed dirt. Not much hope in that.

multiverse theory…

somewhere else

maybe I still have her

This associative thinking is an example of “objective correlative”: the images of the snow and the grave interplay to reveal the speaker’s sadness or inability to deal with a situation in life. However, while the haiku reveals the speaker has lost someone dear, it also holds out the chance of having her again. In other words, hope may exist in hopelessness, as a person who is deeply loved remains in the heart.

Technically speaking, not all of Riutta’s of haibun are composed of prose and haiku. Now and then the prose is replaced by a short free-verse poem, or is rendered in five lines that function more like a tanka.

Civil War

Cold wind.

No more moonlight,

no more answers.

The neighbor’s dog with a bone

that was the other neighbor’s dog.

crows. . .

hard to tell if they are

laughing or not

Another device used by Riutta is the parallel pattern, as in “Early June Rain” or “1970 Something,” In the former, each line is a complete sentence, and the latter contains thirteen adverbial clauses that each starts with the conjunction when and ends with a period. The line starts out innocently enough:

When pushing down dead trees was good enough for our fun.

When old ladies solved most of the problems.

When phones were just for talking and the pink dusks held us captive.

While these reflections celebrate what used to be, the flip side is they’re no longer there—another form of despair. The clauses build and bring to the fore a more despairing situation, and the concluding haiku brings in a note of retribution for human beings:

When a tired old bear could still roam the cold Lake Superior shores hunting for his own death.

driftwood…

such a long way

to stillness

There are many more fine haibun in this book. Unfortunately, the book offers no easy way to return to a poem for rereading. Blessed does not have a table of contents, which is a little inconvenient: readers must turn page after page as if blindfolded. Another conspicuous aspect of the book is its layout. The haibun start on a right-hand page, and because of their shortness all but one appear opposite a blank, unnumbered white page. This forms a pensive frown if one thinks in an eco-friendly way: blank pages may mean superfluous white space. However, questions arise. Does the white space mean blank despair, or despair as blank as a white void? Does it suggest a hopeless situation after one goes through despair, a future to be filled with hope, or a kind of life to explore or live? Or is it simply a printing issue? These may be ruminations, yet page-turning to a blank page seems to resonate with the title, which welcomes interpretations of “almost every despair.”

And those interpretations are well worth reading. Blessed, as Bob Lucky says in his back-cover testimonial, “is Andrew Riutta’s epistle to the world.” It reveals different facets of the author and of our age, which itself offers so many reasons for despair. Read Blessed for relief, for enlightenment, and for more than a little wisdom on how to endure.

About the Reviewer

John Zheng has authored Enforced Rustication in the Chinese Cultural Revolution and published haibun and tanka prose in cho, Haibun Today, Southern Quarterly, and Spillway. He is the author of A Way of Looking, a collection of haibun and tanka prose that won the Gerald Cable Book Award.