Book Review:

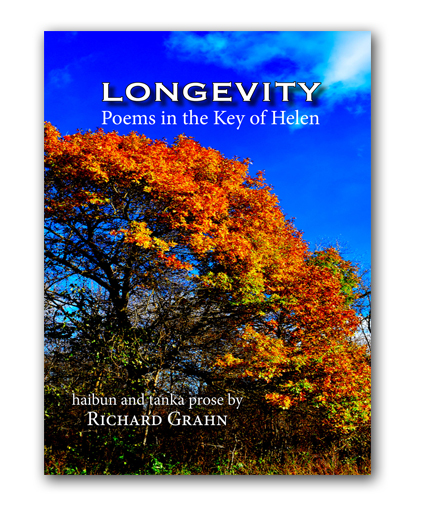

Longevity: Poems in the Key of Helen

By Richard Grahn

Published by Red Moon Press

2022, paperback, 80 pages

ISBN: 978-1-958408-04-9

$20.00 US

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Jenny Ward Angyal

Several themes are woven throughout Richard Grahn’s new book of haibun and tanka prose. The poet’s life is portrayed as a wandering, challenging journey from childhood to creative maturity. Awareness of the passage of time and the shortness of life runs throughout that journey, as does gratitude for the sustenance provided both by memories of the poet’s grandmother and by the redemptive power of art.

The title, Longevity, can mean long life and long service; both were characteristics of the author’s grandmother Helen, to whom the book is dedicated. The book’s subtitle, Poems in the Key of Helen, suggests the degree to which her life determined the tonality or character of the poet’s own life and work, and how solidly she anchored the poet’s peregrinations:

for many years

I have wandered

this earth. . .

a maple stands

where the journey began(from “Stronghold”)

The book’s 30 pieces, evenly divided between tanka prose and haibun, are primarily arranged in three sections. (A final tribute poem, “Forever Gramma,” is printed beside Helen’s newspaper obituary and serves as a coda.) The first section, “Learning to Swim,” includes richly detailed and evocative childhood memories of climbing trees, plunging into a chilly lake at summer camp, and, as in this excerpt from “In the Fields of Forever,” getting delightfully lost among ripening corn:

Some people look at a cornfield and see just a field. I see a haven, ripe with adventure and silky ears to whisper to. Turn left at the ladybug and follow the sun; a kid knows the very best places to hide. The secrets of the maize envelop me. I close my eyes and immerse myself in the roots and tassels, pausing along the winding path laid out for me.

following the footsteps

of a wandering child

the poet

finds a verse

scribbled in the soil

This tanka intimates that the section’s title refers not just to the poet’s development as a child but also as a writer. That theme extends through the section. In ‘Enchanted,’ the poet writes of “stepping out onto the page” with his muse for partner; three tanka following the prose in one-two-three waltz-time. And in “Battle Cry,” the poet settles at his desk and prepares for what’s ahead:

I tilt my head left to right to left, then forward and back to forward. Roll it around. Shrug my shoulders down, then up, down, then up. Fingers squeeze, stretch, squeeze, stretch. Rotate wrists—bend at the knees, bend, stand and bend. Now at the waist, touch my toes, breathing in, breathing out. Shake it, shake it. Put on some jazz — the needle in the groove popping and crackling.

I settle in at my desk.The pen is mightier . . . it’s so proclaimed. I touch the keys and set out to prove it.

Worldwide Love

on the nightly news—

new species

Although he believes strongly in the power of poetry, Richard Grahn can never be accused of taking himself too seriously. Self-deprecating humor and a highly original way of seeing the world are among his trademarks.

Even as the poet learns to swim through childhood and into his life as a writer, he uses the swimming metaphor in another way, as well. In “Breaststroke,” he observes that “Time swims but does not tread water” and concludes that, even as the clock inexorably ticks, he prefers surfing the waves over remaining stuck either in the womb or in senescence. He’ll take his chances in the tide, vulnerable but fully alive.

The book’s brief second section, consisting of four tanka prose, is called simply “Helen” after the author’s grandmother. In a tribute called “Center of the Universe,” Grahn writes

I can remember the creaky sequence of five doors opening and closing through the garage and into the kitchen . . . there you were on the foundation of your dreams raising a home where I could come alive. . .

Deeply resonant and relatable memories of the haven called home continue in “Stronghold,” where the poet, looking back, reflects with gratitude that “there’s always this place to ease my mind.” We all need places to feel at ease, but this may have been especially true of the author: The book’s third and longest section, called “Up From Here,” documents the struggles of a mind much in need of easing. It begins with “Adjustment Disorder”:

I’m floating in an uncharted region of my mind. There are no faces in the portraits on these walls. Hitchhiked here from the medulla oblongata. Found myself sloshing it up at the pituitary gland. Provisioned further at the hippocampus and hypothalamus before setting off on foot to chase down a neuron, was told it ventured this way from nowhere, destroyed everything. My feet are gone. Where I’m going, I’m gone. But I’ve been there before. Not going again.

poems

on padded walls—

the orderly barks, Stop!

but I refuse

to surrender the crayon

The prose is a free-wheeling, stream-of-consciousness investigation into the relationship between mind and brain, deeply serious yet leavened by Grahn’s irrepressible sense of humor. Sculptor, musician, and poet, he has never yet surrendered the crayon as he continues to explore and celebrate the redemptive power of creativity.

The following piece, a haibun titled “The Other Side of Midnight: A Medication Journal Entry,” reflects on the impact of medication on that essential and potentially healing creativity: “When I’m in my manic state, thoughts flow over the dam in a steady stream. In my supposedly-appropriately-medicated state, the proverbial spillway seems to run a bit dry.” He later captures the bi-polar state with the following haiku:

awake in a dream—

reality bites

my dog

The poet then visualizes a lonely bridge, with a fairy clutching a medicine box standing in the middle:

Here, there is no turning back. Here, there is no empathy, no emotion played away on the black and white keys of a grand piano. Here I’m just another cardboard silhouette casually propped up in a department store window. Here, there is no shore. Time traces fingerprints on the window. The window opens and I step out onto the crowded street.

got a problem?

take a pill . . .

follow the winding stream

The kaleidoscope of shifting images and metaphors sweeps the reader right into the heart-mind of the painful and perplexing dilemma, while awareness of the passage of time heightens the tension.

Whole decades pass in the next piece, “The Climb,” which expands upon this theme by portraying the life and mental trajectory of a protagonist named “Gabe.” Five-and-a-half pages long, the tanka prose begins by presenting Gabe as someone who “always had an artist’s bent” but avoided writing. As a youth, his creativity found an outlet through Lincoln Logs and Erector sets; by constructing “cities” from sand; by rearranging his bedroom every other day. Readers follow Gabe’s early life, from these initial pursuits to being sent off to Maine to live with various relatives, through stays at summer camp and life in junior high, where he connects with music and running (“sometimes the wind was in his face, other times at his back”). He finds a girl named Susan, as well as loss:

The universe took her away. There was only running left. Not knowing where to run, Gabe took his harmonica just in case.

gazing

at the desert’s edge

compass pointing

into the wind

eyes filled with sandWeightless, that’s how it felt. Unattached. Drifting toward his roots, then recoiling. The army fixed all that. They took away his harmonica and introduced him to marijuana, LSD, and meth. He responded by drawing pictures inside the drawer in his room, copying images from the covers on packets of papers he used when rolling joints.

Then Gabe falls in love with education, reconnects with music, becomes a prolific sculptor and computer programmer. . . until “the crash, this time plunging deep into the depression pool, relationship gone awry, deaths, a job and its perks all lost, hospital stays—more than a couple of Jokers in his deck.” Hospitalized, he begins writing poetry, and the gift of a laptop finds him writing obsessively for hours a day. Through it, he finds redemption:

thanks his stars for another day. He’s learning to balance on a spinning earth, spreading his stories like pollen on a summer breeze.

a flutter

of oak leaves —

the lightness

of shadows dancing

in this Illinois sunset

In the haibun “Light as Air,” the poet muses on the zigzagging flight of a white butterfly and comments that “I have felt like that insect for most of my life, flitting around, looking for the perfect place to rest.” His flitting can be seen throughout many of the other haibun in this section as he recounts the people and places he’s known. It takes him back “Inside the Gold Mine” of his grandparents’ basement, a treasure-house of jams and jellies, a workbench and a hand-cranked wringer washer, rocks and minerals, stories and memories. As he notes:

These days I find myself spending more time in the basement. It’s quality time for me, springtime in my mind.

old songs

playing on the radio . . .

a pear blossom opens

But the journey to this peaceful place has not been easy. In “Baggage Claim” the poet writes

I’ve . . . tried to exorcise the demon with voodoo, burned candles at the altar, told my shrink I didn’t want it, tried to flush it down the toilet, throw it out with the trash. Ran it through the laundry but the stain just won’t come out.

Finally, he picks up a permanent marker (remember that crayon he wouldn’t surrender?) and scrawls on the wall in capital letters “I FORGIVE MYSELF.”

donated his suitcase

to Goodwill . . .

traveling light

Thus the act of writing, insightfully applied to the writer’s own story, becomes the means of vanquishing demons. Leaving baggage behind, the writer is free to travel light, with good will toward himself and toward the world.

Longevity is the story of a long and difficult journey, traversing astonishing heights and depths, told with honesty and humor. It is a testament to the human spirit and the redemptive power of creativity in all its forms. It is a reminder to the reader to dump the baggage, watch more butterflies, spread your stories, and most of all to cherish the moment:

a glissando of chirps

from the land of dreams

casting spells . . .

as bones rattle

the forest whispers

I rise again

a simple reminder

to cradle each moment

to listen

before it’s gone(from “Snapshots”)

This beautiful braided tanka captures in ten lines the heart of the poet’s story—as bones rattle / I rise again—while also reminding us to listen to the land of dreams and to create our lives and our stories from that ephemeral place before it’s gone. I highly recommend accompanying Richard Grahn on each step of his remarkable journey. You’ll be glad you did.

About the Reviewer

Jenny Ward Angyal is the author of two tanka collections, Moonlight on Water and Only the Dance, and co-author of Beetles & Stars: Tanka Triptychs. She currently serves as tanka editor of Under the Basho and is global moderator of Inkstone Poetry Forum.

What a beautiful , sensitive and overarching review, one that captures the essence of both the book and the poet. Helen would be proud.