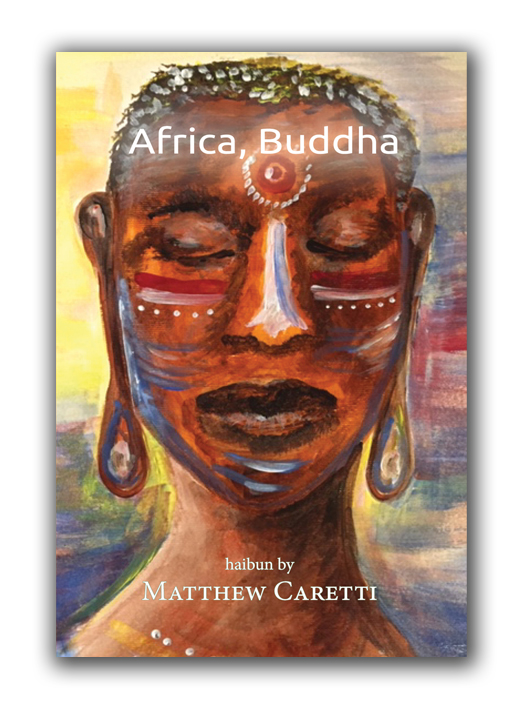

Book Review: Africa, Buddha

By Matthew Caretti

Published by Red Moon Press

2022, paperback, unpaginated

ISBN 978-1-947271-89-0

$20.00 US

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Bob Lucky

As an erstwhile itinerant international school teacher, I can identify with much in Matthew Caretti’s Africa, Buddha, especially the cross-firing of cultural values and the very fluid idea of what education means. There is also much I can only imagine. For example, I’m not a failed Buddhist monk, which is one way Caretti identifies himself in this collection. The journey he takes us on is about discovering what that means to him and where it may take him.

The book is divided into four sections. The fourth section, “After Words,” serves merely to point us back down the path. The title of this section is no typo. In some ways, Caretti uses language, words, as a dowsing stick to find his path. A linguistic serendipity, as in

Tea with a Nun

“What will you do now?” she asks.

“I will teach.”

“Where?”

“Yes. Where?”

“I have friends in Malaysia.”

“Malaysia then.”

silence

how the river

bends it

Working “back words” through the text, one sees that the path the author is on is often dependent upon the words of others — administrators who reassign him, colleagues who might be manipulating him, a monk who mentors him, students who teach him, and a continent that enchants him. What this tells us about the author is that he listens, tries to understand.

Part One, “Here to There,” is the beginning of this journey and takes us from the renunciation of his monkhood back to Africa, where he had earlier been a Peace Corps volunteer. (Anyone who’s traveled by bus in Africa will relate to several of the haibun in this section.) A bit adrift, Caretti is looking for a cultural identity perhaps. On a bus trip he meets another pilgrim of a pronounced Biblical slant, both of them “in search of a new tribe” (“Diaspora”). Later, in the National Gallery in Harare, he quotes the cultural theorist Stuart Hall: “[W]e are ‘positioned by, and position ourselves within, narratives of the past.’” In other words, renunciation of any kind is a hard row to hoe.

Mistake after Mistake, the Unmistaken Path

I arrive in Malawi. At the orphanage. Head first to the temple. Offer three bows. Three prostrations. Three sticks of incense. Then make three wishes.

To benefit the children here.

To understand why I left the monastery.

To discover a new path.

temple gate

the orphan boy shoots

and scores

I want to believe it’s a three-point shot.

In Part Two, “The Warm Heart,” Caretti is beginning to find that path, that identity that he seeks. And, of course, with a hiccup here and there, he both discovers the path and the nature of the path. At least that’s how I read it. He gets derailed. But not all is lost. After a year in Malawi, he’s transferred to Lesotho. As he observes of his farewell ceremony in “Boddhisattva Path”—

[W]here in Africa there is a formal gathering, there are speeches. Many of them. Mine the last. So there in the great hall, with my final words, an unyielding reminder to the children—and a tacit scolding meant for some of our more pious overseas volunteers—Don’t worry about being a Buddhist. Just work on becoming a buddha.

sudden squall

incense smoke swirls

into nothing

In Part Three, “Towards the Sky,” he begins to settle in Lesotho, to come to grips with what his institution, a Buddhist foundation operating orphanages in Africa, is trying to accomplish and with what he is trying to realize as a human being within the system. There is conflict.

I Take the Threatening Stick

. . . from the fist of the teacher. Ask the child to hold onto each end. Grip between her tiny hands and lift her up. Past my chest and neck. By the time her eyes reach mine tears have dried. A frown become a smile. Then higher. Over my head. All squeals and laughter. The others, too. Queuing up for the next take-off.

learning how

to hold a pencil

blossom moon

Like many a teacher or administrator in a similar situation, he begins to see himself at home, to identify with the orphans in the school, the local culture. Yet, before he knows it, things go awry, as things are wont to do. The final haibun in this section is heart-wrenching.

Making a Life

I slowly come to imagine myself here forever. Half monk. Half father. Learning to be a leader. Conjuring some vision of harmony—local staff, overseas volunteers and the children bound together in purpose. I allow myself to settle ever deeper. To sprout roots. Friends and familiar faces. Connections at other NGOs. In government offices. On the street.

the hawker

adds an extra mango

summer breezeThen the sudden news of discord at the organization’s headquarters. A mass resignation from our board of directors, including my mentor. She writes of a negation of the reforms we had begun. Shares concerns about the founder’s vision. I am left wondering, again, about right livelihood.

first plane out

my bags half full

half empty

As the haibun I’ve quoted above demonstrate, Caretti is not only fond of but also adept at using the fragment, the phrase, the dependent clause, the word as an independent thought. And where he breaks sentences into fragments is often in those places we commonly chunk phrases when we read. There is little.of.that.over.done use of periods for emphasis; rather, Caretti uses fragments to enhance our usual reading strategy. Sometimes he chunks the prose of a sentence. Into prepositional phrases. Noun phrases. Etc. Sometimes omits the subject of sentences. This is surprisingly effective in that it slows the reader down and occasionally creates tension. At times it seems his haiku flow more effortlessly than his prose, but one is reminded of Wendell Berry’s observation that “The impeded stream is the one that sings.” And Caretti’s prose can sing, is quirkily melodic at times. In the haibun below, there a fourteen periods/full stops but only five grammatically complete sentences. I read less and less about the haiku nature of haibun prose these days, but I suspect Caretti has found his haibun voice.

American Independence Day in Lesotho

The TV room is new. The one hundred channels of satellite connectivity strictly supervised. Screen time limited. Only the older ones allowed in. And yet the children are happy here. The NGO decided they need to know the world. Current events. News. So we shiver together in the antipodal winter. Watch a segment on the separation of immigrant families at America’s southern border. They know this is my homeland. Turn to me. A sudden sorrow in their eyes. In my own.

fourth of july

orphans unravel

a stars & stripes scarf

The 51 haibun in Africa, Buddha are of a piece, each one connected to the next in Caretti’s account of his pilgrimage or search. Although many of the haibun were previously published as independent pieces, everything comes together here as a seamless whole. And the narrator/author acts as an ethnographer explaining for the reader various cultural aspects. That may explain the copious footnotes, which can be an unnecessary distraction at times. Caretti uses words and phrases from several Bantu languages as well as Pali and Mandarin in both the prose and the haiku. In the prose, he often goes for a gloss, which is efficient and doesn’t disrupt the flow for the reader, but most foreign terms in the haiku are footnoted, a practice that can take the wind out of a one-breath poem.

Often this footnoting isn’t needed. For example, the first haiku in “Johannesburg” reads

tsotsis stole even his beers

Tsotsis is footnoted as South African slang for “thugs.” Thugs would have worked just as well and obviated the need for a footnote. Even better, use tsotsis and forget the footnote. The verb “stole” is all the reader needs to work out the meaning. In another haibun, “Triple Refuge,” Caretti avoids a footnote by using an English description of an object rather than a local word, phutu or potjie:

three-legged pot the blackening of sundown mountains

This is an issue for any writer using non-English words and phrases to add specific detail or create atmosphere in an English-language haiku. The two strategies above — having a context that reveals the meaning of the foreign term or using an apt English description or translation —are workable ways of avoiding a footnote. Here’s a haiku from “Settling In” that illustrates what can go wrong with footnoting a haiku.

seana marena

gentle wave

of the shepherd

And here’s the footnote: “Seana marena, or Basotho blankets, are the traditional colorful, wool (now often fleece) mantles worn by herders in Lesotho. They have more recently become known worldwide via the film Black Panther.” This is interesting information, but in no way does it add to the haiku or the reader’s understanding of the haiku and its link and shift with the prose. It’s almost like explaining a joke.

This is a quibble that shouldn’t distract from the quality of this collection. I bring it up because with more haibun being written in world Englishes, this is perhaps the moment for writers to consider seriously their audiences, which are worldwide and multilingual (the United States generally excepted, I’m afraid). Caretti is right to assume that most of his readers will not be familiar with Sesotho or Chichewa. What to do? Perhaps we should follow the lead of the Modernists like James Joyce and T.S. Eliot and just stir the linguistic pot. All I can say with certainty is that a haiku with a footnote is hobbled.

Finally, I think it’s fair to say that China is the elephant in the room in this collection. In academia, generally speaking, the presence of China in Africa is characterized as neo-colonial. However, some Africans I know see benefits in the Chinese presence — schools, hospitals, roads—which does have that colonial rationalization about it. The Chinese are not doing those good deeds for nothing any more than the British, the French, and the Portuguese, to mention a few, were. There are several instances where Caretti touches on the cultural dissonances, but nowhere more directly than here:

Confucius & the Sangoma

The orphans are flummoxed by their foreign benefactors. So many unfamiliar rules here. No hands in pockets. Hold your bowl with a dragon’s maw grip. Bow to every teacher. To begin class. To end it. These dictates too often tangled in the word rather than the spirit. But slowly the edicts of Confucius fade on the photocopied sheet pasted to the classroom wall. The drums beyond the compound fence sound again. The children listen. Hear the sangoma commune with the spirits of their ancestors. Understand fragments of the shaman’s prophecy. And begin to remember where they are. Who they are.

cooing

African pigeons

under the day moon

Perhaps it all comes back to Stuart Hall, of how we’re positioned in narratives of the past. And of the various ways those narratives can be rewritten, with or without our consent. Africa, Buddha is a glimpse of Caretti’s life story in progress. It’s compelling. It also makes a strong case for haibun as an ideal vehicle for memoir. But you have to imagine how much he left out, what he left out, which is the art of memoir.

Work Cited:

Berry, Wendell. “The Real Work.” Standing by Words. Counterpoint, 1983.

About the Reviewer

Bob Lucky is the author most recently of My Thology: Not Always True But Always Truth (Cyberwit, 2019) and the chapbook Conversation Starters in a Language No One Speaks (SurVision Books, 2018), which was a winner of the James Tate Poetry Prize in 2018. Lucky lives in Portugal, where he is working his way through all the regional cheeses and wines.