From “Marbles” in Bar Resbel by Bouwe Brouwer

Book Review:

Bar Resbel: A Week on an Island

By Bouwe Brouwer

Published by The Old Sailer Press, Sneak, The Netherlands

2021, Paperback

€15.00 for English Edition

€10.00 for Dutch Edition

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Patricia Prime

Bouwe Brouwer lives in the town of Saak in the Netherlands. A primary school teacher at a refugee camp, he is also a talented writer and photographer. In Bar Resbel, he combines those two talents to create ekphrastic haibun that together compose a “frame story”—14 episodes from the author’s trip to Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

Many of the stories are told in the bar that gives the book its title, and through them we slowly meet the locals: Elian and Nesto, the two brothers who own Bar Resbel; Elian’s two sons, Colon and Cortez; Fidel, a taxi driver whose intimate life feels epic in scope; and various bar patrons (including the writer Raymond Chandler). There’s something about this heart-warming stories that makes the characters come alive and leads to the best kind of ekphrastic poetry.

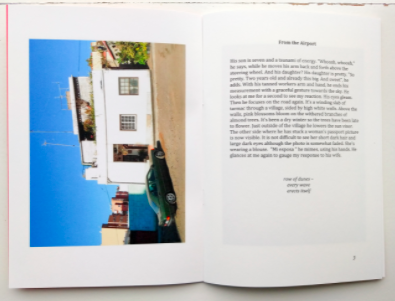

The haibun in Bar Resbel follow a similar pattern: a one-paragraph haibun followed by a haiku, both of which face a photograph on the opposite page. Brouwer writes with great strength and sincerity, and his words provide the same intensity of color as found in the photos. The collection starts with “From the Airport,” in which Fidel has picked up the author from the airport and, while driving him to the village, describes his family with delight. Fidel’s depiction of his children captures his exuberance:

His son is seven and a tsunami of energy. “Whoosh, whoosh”, he says, while he moves his arm back and forth above the steering wheel. And his daughter? His daughter is pretty. “So pretty. Two years old and already this big. And sweet!” he adds. With his tanned worker’s arm and hand, he ends his measurement with a graceful gesture towards the sky. He looks at me for a second to see my reaction. His eyes gleam.

Opposite the haibun, a color photo depicts a dusty sedan (presumably the one driven by Fidel) parked in front of a modest, whitewashed house. Is this where Fidel and his family live? It’s not clear, but Brouwer’s words enhance the image indirectly.

This indirect approach between photo and haibun continues throughout the book. In “Wine,” Elian relates a story about his father and a long-held gift:

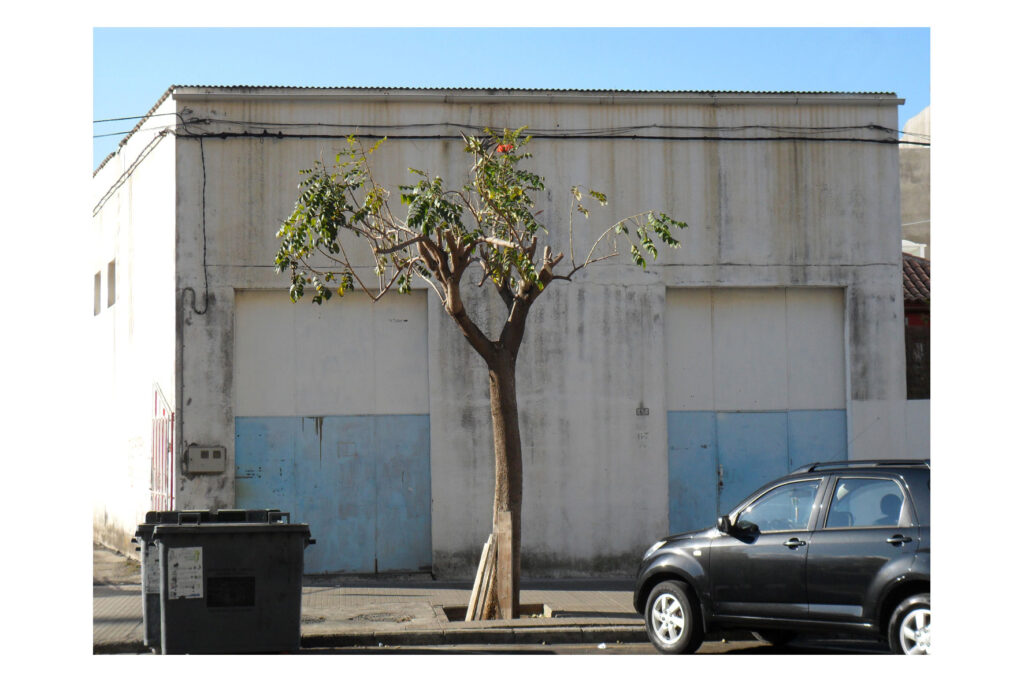

The brothers are at work. They’re each wearing a red polo shirt with thin grey stripes. That’s what they both wear every day. It’s their work clothes; a uniform. While I order an espresso from the youngest, the older brother is talking to one of their regular visitors. He tells him that their father was saving a bottle of wine for a special occasion, in an antiqe cabinet in the cellar. The bottle was a present from his childhood friend when he graduated. The friend had died too young. Finally, just after his father passed away, he was almost 83, the brother had opened the bottle and poured himself half a glass. The wine had become undrinkable.

residential apartment‚ in every window a sunset

The companion photo shows neither a skyscraper nor a sunset, but a dirty concrete building in daylight:

At street level, two grimy sky-blue squares punctuate the building’s worn, windowless exterior; in one, a door is visible. Where in the haiku the sunset picks up on the passing of lives and dreams, the sky-blue panels here serve somewhat the same purpose—although they also have a hint of hope and perseverance. The image makes the poetry more acute, and the haibun adds a further dimension to the image.

Personal and private shades are present throughout this collection. In “Nesto,” the reader meets Elian’s taciturn younger brother, for whom “words won’t seem to pass from his bristly pale brown mustache,” and who always “looks like he’s somewhere else.” (A later haibun gives readers a glimpse of Nesto’s difficult early years: from 15 to 21, he lived apart from his family on another island, surviving on odd jobs and handouts.) Elian’s children appear in the haibun “Marbles,” which presents a delightful picture of the two boys following a game on the terrace, and the hard lesson the older one tries to impart (“You just have to play it, not aim too much”). There is Arlo, the “dreamer,” who comes each day to the bar at 11 o’clock to fold napkins, and the stranger with a face like a “desert landscape” accompaned by an enormous sheep dog.

And there is Fidel, for whom a miniature portrait emerges; How as a little boy he helped his father carry bananas from plantatation to plantation, along a path of solidified lava; how his father left the family when he was four years old; how he drives his cab, steering with his knees while rolling a cigarette or honking three times when passing the house where he lives with his wife and two children. In “The Guest,” he is described as “stting bent forward behind the bar, hidden behind a big glass of beer. Like he’s trying to see the world through the gold-yellow liquid.” And in “The Writer,” he meets the author Raymond Chandler:

With a deep sigh Fidel leets himself slide across the bar and puts his cheek on the cold top. He blinks a couple of times. “Every day it’s the same thing,” he mumbles. “How do you do it Mr. Chandler?” An elderly American man stops writing. He puts down his pen and seems to focus his greyish blue eyes on something that’s far behind the back wall of the bar. He nods his head slightly and starts to speak. “Sometimes I would like to do something differently. I get up in the morning and tell myself: today I will write a poem. Maybe a travel story, something autobiographical. I’ll just start and I will see where it will take me. But every time it turns into a detective story. Whatever I try to do, that’s what it will turn into. What you’ve got are your stories. You may like it or not. But they’re yours.”

excavation a lizard hides underneath a rock

The accompanying image picks upon the haiku’s setting and leaves the reader wondering what hidden surprises it might hold.

With a distinctive voice and gentle wit, Brouwer has taken the stories he found on the island (with all their surprises) and made them his own. In Bar Resbel, he makes them ours. This is a bar, and a collection, you’ll want to visit.

About the Author

Patricia Prime is co-editor of the NZ haiku journal Kokako. She is the articles editor for contemporary haibun online and also a reviewer for Atlas Poetica, Takahe, and other journals.