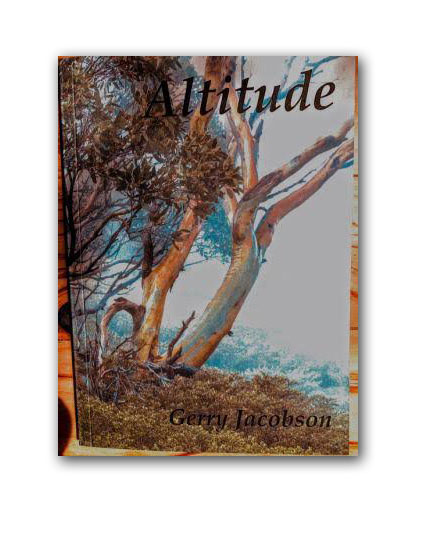

Book Review: Altitude

By Gerry Jacobson

Published by Hill Corner Press

Canberra, Australia

2021, Paperback, 41 pp.

ISBN 978-0-6484454-1-8

$20.00

To Order: E-mail Gerry Jacobson

Reviewed by Patricia Prime

In Altitude, Gerry Jacobson takes the reader with him on his high-country adventures in Australia and beyond, stringing them together in an eloquent layering of tanka prose and haibun.

Through some of the hikes, readers meet members of Jacobson’s family and learn more about the poet himself. The first piece, “Reaching Up,” features a mountain climb while he’s on holiday with his granddaughter Rosa and his son.

We leave the holiday house at 6 am. It’s Rosa, her Dad, and me; the other children are still asleep. There’s a warm wind on the climb and I’m slow, but Rosa stops for photo and I catch up. Brownbarrel* reaches for the sky, and there’s fresh wombat poo.

*Eucalyptus fastigata

With a few well-chosen details, Jacobson documents the adventure and, in particular, captures the liveliness and personality of his granddaughter, who is interested in more than just taking pictures. “Why is wombat poo square?”she questions her all-knowing Dad, who quotes the latest research. Later, when Jacobson asks Rosa if this is her first mountain, she emphatically states “No.” The piece ends with this delightful tanka:

all the rhythms of walking Earth … uphill plod and bounced descent . . . rhythm of the body knowing

In the haibun “The First Time I Saw Your Face,” Jacobson writes about Rae Marshall, who is now his wife. He describes the way they met, prior to a group bushwalk, when he went around to check on new walkers and make sure they had the right gear:

It was the first time I ever saw your face. Were you wearing a soft grey-blue jumper that highlighted hazel eyes? Rae Marshall’s eyes? This knock on the door was a turning point in my life. For a while we were part of a group of friends, then we drifted into being girlfriend/boyfriend. That was April 1962, exactly 59 years ago. The wheel of the year keeps turning. It’s autumn again now, and what have we drifted into?

reaching out beyond my fingertips this crowded room

And in “Where is Mount Kinabalu?” readers learn more about Jacobson’s early life, when a phone call from a London professor leads him to recall one of his early professional adventures:

Faded black ad white photos of a young Australian geologist with a flowing beard. A golden time, the best of times. We share it, Rae and I, newly married. Assigned to Sabah by the Australian equivalent of Peace Corps. Rae works as a physio at the local hospital. I spend much of my time clambering up and around a great mountain.

Jacobson’s storytelling is effective in its simplicity. When describing the climb up Mounta Kinabalu, for example, the crisp narrative says just enough for the reader to visualise the expedition and what the team undergoes.

With a visiting scientific expedition, we climb up the eastern side of the mountain, and out on the unexplored north ridge. Camp on top for a week or so. I map granite structures and also glacial features. The mountain was once capped by ice. We all get swollen joints from the sojourn at 4,000 metres.

The poet is also skilled at conveying atmosphere. The title poem “Altitude” begins with a breathless description of the snow-covered mountain:

All the flowers of the mountain up there wandering the granite tors snow gums tussock bogs sedge and reed and flowers under snow drifts melting crunch of snow as my boot sinks in windy sadness of burnt snowgrass ash dust in the air in my eyes can hardly see the next peak where am I?

altitude thirteen hundred metres stark burnt trunks of alpine ash desolate and fierce

Jacobson stands on a peak and continues his contemplation in that same stream-of-consciousness style: “nibbling drink from water bottle rough granite under bum seeing the route how does body know to swing off the peak sway down that ridge curve into the valley wade through the heath bounce over tussock sink down by the stream running water blessed in this droughty land.” The piece ends with this lovely tanka, which draws the majestic description of the mountain to a peaceful climax:

deep night

in silent mountains . . .

I wake

to gentle sunlight

on branches of a snow gum

One of the lengthiest tanka prose pieces is “The Emptiness of Sunday Afternoon,” which contains a reminder of the span of both geological time and human history. It begins:

Head down, I carry a heavy pack up the steep climb out of the Cotter valley towards Mt Bimbert. Trying to keep up with Graham and others, my eyes are fixed on the track. Almost touching it. Suddenly a stone axe-head embedded in the mud. Someone has been here before me on this remote track. Hundreds of years before. Thousands?

He later reflects on his own life and aging in “Granite Country,” a haibun about the author’s visit to the remote Pitjantjatjara lands, where he is engaged in an underwater study.

And now my right hip is stiffening. I’m not fit enough for the Wednesday Walks. Will I bushwalk again? Will I get back to my country? Or will I have to use a Land Cruiser like so many of the brothers and sisters out there? And get some whitefella* to drive me.

*A Caucasian person, especially as opposed to an Aboriginal Australian

However, the author is not quite done yet with his outdoor adventures, as he makes clear in “Hughie” with a bit of humor. After looking at some “faded black and white photos of people milling around a smoky fire,” he reflects:

Those were the days. But I’m still doing it. On an English walk last July, I sleep out one night, enjoying the moonlight. Then about 2 am I feel the gentle kiss of raindrops. Snuggling deep, I pull something over my head and go back to sleep. In the morning the sleeping bag is sodden; I am sodden; all my gear is sodden.

I’m calling out to English clouds Send ‘er down, Hughie! but oh . . . ‘oly shit ‘e really does

Altitude also contains several tanka sequences in the collection. Jacobson makes the linking process between prose and tanka seem natural, and his longer sequences read like miniature stories. Here is one example, “I hold the dream”:

late summer

in the high country

sweating up the spur

but where have all

the march flies gone

cresting the ridge

bare rock and tussock

breathless

I hold the dream

of fire in the snow

left knee wobbly

balance not quite there

but yet

my body remembers

ten thousand descents

draining

my water bottle

on the river bank

tea tree and manna gum

cast a scant shade

a dragonfly

hovers above the dark pool

in Thredbo river

diving in I become

a silver flashing trout

In the final tanka prose, “In the Highest,” the poet is again accompanied by his son and granddaughter, this time as they climb Mount Kosciuszko. They are caught in a blizzard and shelter inside a cafe at the top of the chairlift. Jacobson writes, “We’ll come back in summer, covid permitting. And Rosa likes the idea of going to Mt. Everest.” The tanka prose ends with this tanka:

a climbing dream -

loose block under my hands

I reach across

for a good jug to hold

but I can’t climb down

Throughout the collection, Jacobson depicts the mountains, the scenery, the people, and his family in a way that feels true. Each tanka prose and haibun is unique, but together connect us to the poet, his life, and his adventures. In Altitude, we’re climbing high with him.

About the Reviewer

Patricia Prime is co-editor of the NZ haiku journal Kokako. She is the articles editor for contemporary haibun online and also a reviewer for Atlas Poetica, Takahe, and other journals.