Emma Cortellessa

Haiga: A Successful Meeting of Image and Text

In Japan and elsewhere, people have long sought out ways to combine images and text. The synergy between these two forms of expression, both visual and literary, often sharpens their impact and makes them more powerful.

But the integration of words and images is not so easy—they must highlight and enhance each other. One field in which this relationship is particularly intriguing is poetry. The flexibility of poetry, ranging from the mysteriously complex to the refreshingly simple, offers many opportunities for artists, writers, and designers to integrate images; but it can often be a delicate process.

Haiga (also known as haikai drawing), is a Japanese form of painting that combines a sumi-e Japanese ink brush painting and a haiku. The rise in popularity of haiga arose out of 17th century Japanese stylistic conventions. The combination of visual symbols and literature added a significant aspect to Japanese aesthetics. Matsuo Bashō, Yosa Buson, and Kobayashi Issa are considered masters of haiga and haiku.

Upon further review of their collective oeuvre, it is easy to see why. Not only did their influence change the landscape of Japanese painting and poetry, but their work remains beautiful in its simplicity even today.

bare willow a dried up, clear stream— rocks here and there –Yosa Buson–

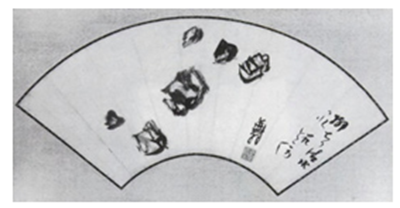

Figure 1 Buson, Yosa. Rock Haiga. Private Collection, Japan. The Poet-Painters: Buson and His Followers by Calvin Leonard French, p. 75

In Buson’s work, Rock Haiga, pictured to the left, the black ink of the poem accompanies an ink drawing of rocks. Literary scholar and author Stephen Addiss notes that because haiga paintings were created with the same brush, the act of haiga painting was a “natural activity” for its practitioners.

Here, in Buson’s piece, the rocks mirror their places in the stream. The painting and text work as one complete image while, at the same time, both can be appreciated separately. For modern Western viewers, the rock in the middle of the fan is the boldest, thereby attracting our attention first. Slowly, our eyes will be guided by the rocks in the stream to the text on the right hand side. On the other hand, if we view this haiga through the lens of people in 17th century Japan (who also were Buson’s audience at the time), their eye may be so inclined to view the text first. When written vertically, Japanese writing is read starting right to left. In this view, the text may take precedence over the image, maintaining a delicate visual hierarchy.

the nightingale hanging upside down— first song of spring –Takarai Kikaku–

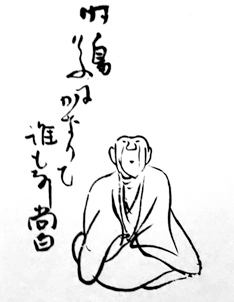

Figure 2 Buson, Yosa. Haikai Sanjūrokkasen. Private Collection, Japan. The Poet-Painters: Buson and His Followers by Calvin Leonard French, p. 67.

While it seems reasonable that a painting of rocks should accompany a poem that makes note of them, sometimes haiga intentionally includes images that don’t link visually with its poem. Take, for example, Buson’s Haikai Sanjūrokkasen (Thirty-six Master Poets of Haikai) series. In this series, Buson painted 36 disciples of Bashō alongside their poems. This anthology is Buson’s way of paying tribute to his predecessors. Each poet, as it were, represents a step in the haiku tradition. In this instance, Buson refers to famed 17th century poet, Takarai Kikaku. However, It’s also possible to view the poem in a deeper context. The nightingale can be seen as a metaphor for a haiku poet singing from every conceivable angle, even upside down. This coincides with the humorous aspect of haiku, as if Buson is both paying tribute to his fellow poets as well as gently ribbing them.

When it grows old its voice becomes plaintive— katydid –Chigetsu–

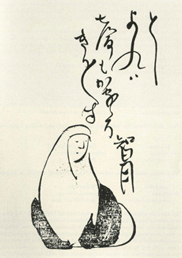

Figure 3 Buson, Yosa. Portrait of Chigetsu, Private Collection, Japan. Haiga: Takebe Socho and the Haiku Painting Tradition. p. 47

Buson’s Haikai Sanjūrokkasen portraits also work beyond pure portraiture. Here, Buson depicts the poet Chigetsu, a disciple of Bashō who became a nun. The calligraphy here is noticeably curvier, and flows gracefully with the portrait of her. The text follows her figure like drops of rain on the page. Even in black and white, there is a feeling of tranquility and somberness in the image. Beyond this, the haiga gives the audience an overall impression of Chigetsu and her oeuvre. The text and image work together to form a narrative.

While haiga can sometimes be mysterious, it nonetheless reminds us of one of the most crucial aspects of the relationship between words and images: that is, both complement each other to enhance their respective meaning. Overall, while traditional haiga may not be as widespread today, it remains a beautiful and modest form of painting that has contributed deeply to Japanese artistic and literary traditions as well as the Western world of poetry, art, and design.

In fact, artists and writers today create modern haiga that incorporate photography, watercolor and even film montage. For instance, Australian artist, Ron C. Moss, is also a renowned poet who achieved international success for his haiku. (Moss’s new haiku collection titled Broken Starfish will be released later this month). Moss’s haiga, Starry Night, is one of his best known pieces.

starry night what's left of my life is enough –Ron Moss–

Figure 4. Moss, Ron C., Starry Night. 2011

While Moss is also a critically acclaimed photographer, Starry Night is a prime example of his sumi-e skill. The image, while taking precedence over the text in terms of visual hierarchy, remains supplementary to the poetry. It is an abstract image, only decipherable through his moving words in handwritten black ink. Indeed, while both can stand alone on their artistic merits, they join forces to create an eerie and mysterious piece of art.

While a haiku and a haiga can be appreciated alone on intellectual and/or artistic quality, their combination is a visual feast. Beyond this, haiga reminds artists, writers, and designers that while any image can accompany text, and vice versa, they should maintain the spirit of the other. With this in mind, haiga masters are also design masters who have triumphed over one of the most crucial aspects of design: a successful integration of text and image. Text can operate as an image, just as much as an image can operate as text. Together, they form a whole, balanced picture.

About the Author

Emma Cortellessa is a senior at Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia. She researched and wrote this article while serving as an intern at Turtle Light Press for the summer of 2019. She drew primarily on three books: Stephen Addiss, Haiga: Takebe Sōchō and the Haiku-Painting Tradition, Calvin Leonard French, The Poet-Painters: Buson and His Followers and William Higginson, The Haiku Handbook.

Signed copies of Moss’s new haiku book, Broken Starfish, may be purchased directly from Moss by contacting him at ronmoss8@gmail.com.

Permission to reprint this article was given by Turtle LIght Press and the author.