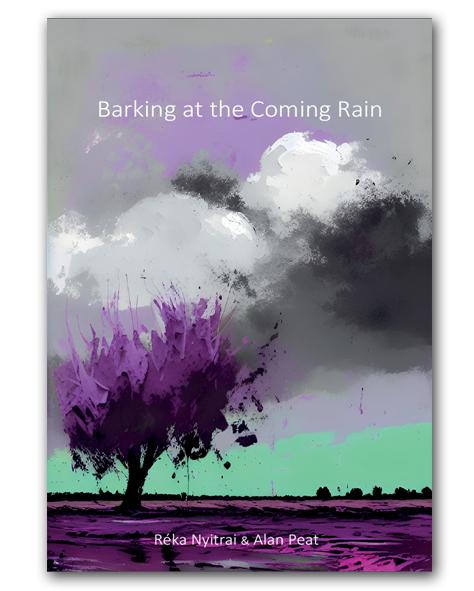

Book Review: Barking at the Coming Rain

By Réka Nyitrai & Alan Peat

Uxbridge, United Kingdom

2023, Paperback, 74 pages

ISBN: 978-1-912773-57-2

$15.00 / €14.00 / £12.00

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Rich Youmans

Given haiku’s roots in renga, it’s not unusual to see haibun writers combine their talents. Often in such collaborations, the lines of demarcation are noted; whether by alternating regular and italic fonts or initializing each individual contribution, the authors make clear who wrote what. Not so with Réka Nyitrai and Alan Peat. As they write in their new book of ekphrastic haibun, Barking at the Coming Rain,

We each took turns in choosing an artwork by a female surrealist. Réka then wrote a prose piece and Alan added a haiku and title. We then BOTH edited the whole so that every part is the sum of our collective endeavor.

The resulting haibun do indeed have a single voice, despite the fact that the poets’ entire collaboration took place long-distance. (Nyitrai lives in Romania, Peat in the UK, and the authors note that all of the poems were co-written without them “ever meeting face to face or even talking on the phone”). Despite this separation, they were able to synthesize their talents and create a collection in which the haibun not only add new dimensions to the art, but also stand on their own as exemplars of the form.

That isn’t too surprising, given how substantial their talents are. Nyitrai began writing haiku in 2018 and immediately earned acclaim for her idiosyncratic, often surreal voice. Her debut collection, While Dreaming Your Dreams (2020, Mono y Mono Books), won the Haiku Foundation’s Touchstone Award, and she subsequently began to write both prose and lineated poems that displayed the same dream-like approach.

Peat similarly seemed to explode on the haiku scene. An educational consultant who has written several books encouraging children to write creatively, he’s won numerous awards for his haiku and haibun since 2017 (including one of the first Touchstone Awards for individual haibun). He also has a longstanding interest in surrealism, and even co-wrote a catalogue raisonné about the life and “dream-landscapes” of the surrealist John Tunnard.

Nyitrai obviously shares that interest. An index at the back of the book identifies the artwork that led to each haibun, and the choices demonstrate the pair’s broad knowledge of Surrealism and its history. The oldest selection dates back to 1922 (“The Mosquito Died” by Hannah Hoch, a Dada artist who pioneered photomontage) and the most recent is “Tiger Lost in Västerbotten,” a 2022 series of plaster-and-wood sculptures (I, II, III, IV) by the Swedish artist Ellen Macke Alstrom. The authors chose 64 works in all, from which they wrote 59 haibun (a few are based on two works by the same artist).

Those haibun are divided among three sections, each of which has a canine-based title: “Sleeping Dogs,” “Storm-Tossed Dogs,” and “Lying Dogs.” Near as I can tell, the haibun in the first section are more dream-like; those in the second generally revolve around loss, punishment, and threat; and the final section looks at marriage and relationships, with healthy dollops of infidelity, deception, and unrequited longing. Of course, I could be wrong on all counts—surrealism in particular can be a bit hard to pin down. Regardless, I didn’t find the arrangement essential to my appreciation of the collection. For me, each haibun, and its connection to the art, was an experience unto itself.

As you might expect, given the nature of the art, all of the haibun are a bit fantastical. Some have the feel of fables, others are more straightforward prose poems (or as straightforward as you can get, given the topics include a woman who gives birth to a giantess and three dwarfs, a woman who wakes up as a fish, and a wolf that eats poems). One is a sci-fi tale about the aftermath of a war between humans and Martians, in which all the women of Earth are abducted. And some are just, well, strange. Here’s the title piece:

Barking at the coming rain

They say that deep in the forest there is a bird-woman who speaks a language understood only by trodden forefingers. It is a blue language, devoid of happiness. In her beak there is a fountain that must be nourished with coins, and golden eggs. If you happen to drink from its waters, in a blink, you will turn into a tree frog.

glittering silence a young girl slips from her swan's skin

I’m always interested in how poets approach ekphrasis—whether they simply try to describe a piece of art or, better, use the art as a springboard for a new work that expands or deepens the viewer’s understanding. That’s why, on first reading, I didn’t try to connect any of the haibun with the related artwork, but instead analyzed them on their own merits. In the case of this poem, the first thing that made my head snap was not the bird-woman (which maybe says something about my tolerance for the strange), but the reference to “trodden forefingers”—specifically, how they were the only ones to understand the bird-woman’s language. Immediately, I could feel the rational gears in my brain begin to turn. Was this a Braille-like language, perhaps? And why did the fingers have to be trodden? Did they have to go through difficult times in order to best understand that language, like a school of hard knocks?

After introducing the trodden forefingers, the poem shifts back to the bird-woman and her language—how sad it is, how it must be nourished by earthly valuables such as coins and, that favorite of fairy tales, golden eggs. The final sentence is one of transformation—into, of all things, a tree frog. At this point my rational brain waved a white flag, and I simply sat back and enjoyed the imagination at work. More importantly, tried to intuit the paragraph rather than dissect it.

What came through most to me was the idea of transformation and the element of sound—or more specifically, sounds whose meanings are beyond our understanding. That obviously could be applied to the bird-woman’s sad, indecipherable language, but it also fits with the tree frogs’ voluminous peeping, a sound that also can’t be deciphered but is more powerful than the creatures’ near-invisible presence. We were in a realm here beyond words. As for those trodden forefingers, if the idea of Braille was meant (the rational doesn’t go down without a fight), that is the only alphabet that conveys meaning while remaining silent. All of those aspects coalesced in the haiku, which recalled Swan Lake’s story of Odette. Transformed into a swan by an evil sorcerer, Odette turns back at night into a beautiful maiden, her true self revealed in the same way that language reveals one’s thoughts. The title also picks up on the idea of sound that may be indecipherable (at least to humans) but still conveys meaning (in this case, fear of perceived threats by something unknown).

Having read the poem on its own, I looked up its accompanying artwork. “The Heart of the Trodden Forefinger” (1967) was done by the Croatian painter Nives Kavurić-Kurtović, who is acclaimed as the “first female Croatian surrealist.” (Click here to view the art.) I at least now understood where “trodden forefinger” came from, although any connections beyond that were a bit of a stretch. The animal depicted could be a dog (especially the hind legs), and the painting does contain some blue as well as two red hands (and is that a forefinger in the central blue circle?). More likely, the poem simply captures the magical transformations apparent in the painting, and it does so in a way that stands on its own as a work of art.

The same can be said of all of the haibun, although in some cases the literary-visual connections are more obvious. “Table with Bird’s Feet,” a 1983 photograph by Meret Oppenheim that depicts exactly what its title describes, appears as itself in “Cancelled Flights”; given as a gift from the narrator’s ex, the table soon begins an affair with a Persian rug. Helen Chadwick’s “Piss Flowers” (1991–92), 12 sculptures created when the artist and her husband urinated in snow and captured the resulting patterns in plaster and bronze, leads to the haibun “Taking the piss,” which begins with a similar tale of pee immortalization but ends with a comment about gender roles. And in “Plumage from the sky,” Nyitrai and Peat take themes from two paintings by the Belgian surrealist Jane Graverol, “The celestial prison” (1963) and “The suffering of Sappho,” and meld them into a wayward angel’s lament:

I have to admit that I wasn’t good at being an angel. When I was assigned to the post of God’s messenger, I often confused the addresses and delivered the wrong messages. Instead of knuckling down to the job in hand, I read novels and wrote poetry. And later, when I was appointed to guard duty, I either fell asleep or couldn’t resist playing on my phone. I guess it’s no wonder that I ended up in celestial prison. At this very moment, I’m sharing the same cell as Sappho.

silenced dark the cloth that covers the songbird's cage

It’s a humorous piece, but the mention of Sappho hints at not just stifling one’s individual poetic voice, but also one’s sexual orientation. As always, Nyitrai and Peat offer multiple levels of meaning.

I could offer additional examples, but it’s better to experience these works for yourself. So much of art lies in the viewer’s perception, and that’s especially true with surrealism and its ability to make us see things anew (without the pesky confines of reality). Perhaps the collection’s title refers to the authors’ attempt to set in words something that can’t be described but is only felt and is somewhat unsettling. If so, their “barking” is quite eloquent; the more a reader listens, the more becomes clear.

If I had my druthers, the book would include page numbers in the index, so I could more readily find specific haibun. I’d also like to have more guidance in relation to the artwork. That index references only the name of the artwork and the artist, leaving readers to find the actual images for themselves. Although I was able to locate all of them online, some I found only on personal Pinterest or Flickr pages, which makes me wonder about their permanence for future readers. If there are better, more stable venues where the art can be found, noting that would be helpful.

Of course, if I really had my druthers (and a truckload of money), I would have all the paintings reproduced in the book (preferably in full color—make that a tractor-trailerload of money). As it is, I’m just glad to have all of these works collected in one volume, which is handsomely produced by Alba Publishing. It serves not only as a master class in ekphrasis and haibun, but also as a conduit to a quick survey of surrealism over a century’s span. I for one am hoping that Nyitrai and Peat continue their synthesis of talents.

About the Reviewer

Rich Youmans lives on Cape Cod with his wife, Alice. His books include All the Windows Lit (Snapshot Press, 2017) and Head-On (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2018). He is also the co-author, with Roberta Beary and Lew Watts, of Haibun: A Writer’s Guide (Ad Hoc Fiction, 2023).