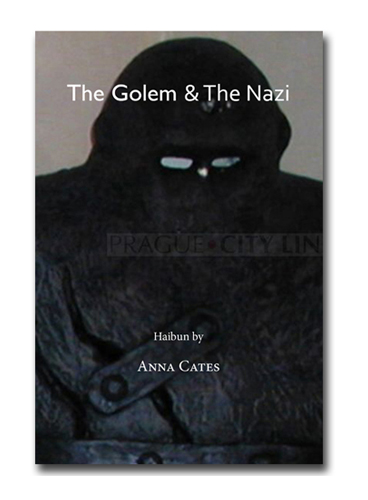

Book Review: The Golem & the Nazi

By Anna Cates

Published by Red Moon Press

Winchester, VA, USA

2019, Paperback, 217 pp.

ISBN: 978-1-947271-48-7

RRP: $15 U.S.

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Patricia Prime

Anna Cates is a graduate of Indiana State University and author of both poetry and fiction, including The Meaning of Life, The Frog King and The Darkroom. She’s also a widely published writer of haibun—many of which have now been collected in her imposing new collection, The Golem & The Nazi. Skillfully honed, the book—especially in its opening sections—takes us deep into the back country of the human psyche, a beautiful-but-uneasy territory often filled with mysticism, mythology, and spiritual mysteries.

The book’s 88 works (mostly haibun with the occasional tanka prose) are divided into four sections. The first, “The Golem and The Nazi,” contains eight poems that seem to focus not just on the Nazis, but also on the nature of human beings and their relationship to evil. The section begins with the title poem, which exemplifies how Cates can quickly shift registers in her writing, creating a sense of unease. The haibun first introduces Adam, a figure who “feels like a golem,” an emblem of the beginning of life. The narrative then dives abruptly into a scene with an Anunnaki (an ancient Mesopotamian god) and a golem, in which “Anunnaki writes the shem, a name for God, on a scrap of papyrus and inserts the honied text into the golem’s mouth.” When the golem comes to life, the Anunnaki writes “emet” (“truth”) on his forehead, so the golem will never tell a lie. The haibun then moves on to World War II and a Nazi who is determined to find the golem. It ends:

He opens the door. He scans the darkness.

He raises his knife, careful on his shiny

black jackboots. When the golem springs

from the shadows, monstrous as a gargoyle,

the Nazi slashes at the inscription, scratching

off the aleph, changing emet to met, truth to

death. The Nazi turns to ash in the synagogue’s

burning, but the golem escapes into the night,

the crystalline, starry, starry night.

blood moon

what a single spark

will do

That escaped golem seems to inform the rest of this section, as the haibun references images and episodes from Nazi history (swastikas, death marches, the Holocaust, and the “Nazi Bell,” an alleged “secret weapon” similar to a flying saucer). This last weapon is featured in “Die Glocke (The Nazi Bell),” where it kills not only a wolf, but everything that surrounds it:

But violet Xerum 525 tears through bridle

and bone. In the zone blood gels, flesh

crystallizes—sparrows, rabbits, lilies die,

and the golden eyes grow hollow, blind.

The last poem in this section, “The Nature of the Beast,” contains a question that perhaps serves as summary. Here is the haibun in full, with its riveting haiku:

My freshman year in college, in Psychology

101, our professor prompted us to debate

the question: Is humanity basically good

or evil? Today, I'm still not sure I have the

answer.

holocaust museum—

the emptiness filling

display case shoes

The next section, “Here There Be Dragons,” contains strains of mysticism, mythology, and folklore throughout. In addition to dragons, the haibun reference witch doctors, wizards, elves, and various gods and mythological figures. The writing can be rich—so much so that at times it resists explication, as if the author wishes to puzzle the reader. For example, the poem that gives this section its title contains a succession of images drawn from the days of pirates, when encounters with dragons were still felt as a real fear for many people. The images cascade:

A parrot squawks at me, muttering the same

phrase repeatedly, a reverie about poetry,

words comprising a vast sea where sail the

golden golds on glistening ships—Plunders,

pillages, and rapes, songs sung to cinch the

irony as bull whips crack with time across backs

or boards, creaking with sea-sickness, decks

slippery with vomited rum.

Elsewhere silence locks like a peg leg, stuck in

nocturnal quicksand—Jungle muddle livid as

God with snakes.

vine-covered cave

on a stone tablet

curious cuneiform

This richness can also be seen in another haibun, “Jekyll or Hyde,” which has its entire prose section—”a quattuordecillion ultramarine buckminsterfullerene hemidemisemiquavering tintinnabulations”—followed by a translation key.

The third section, “Exegesis On Genesis,” continues the exploration begun in the earlier two sections, but this time there seems to be more of a focus not just on myths, legends, religions, and folklore, but on how we humans use them to create frameworks to explain the world and our place in it. Several of the pieces relate origin stories. “Love & Myth,” for example, is based on the Maori story of how the demigod Maui pulled up the Hawaiian islands from the sea. The poem gathers power with the dark, complex figure of Maui, and it ends with a tanka that brings that fire into the present day, where it is eternal:

Before Maori venerated Io, Maui pulled from

the sea land dripping in seashells, forging

islands, stealing fire from the underworld.

He ate the flames like the high priest's

morsel from his servant's instrument.

The priest is untouched. The tapu is unbroken.

The fire ever burns.

tropical bird calls

the last mango falls

Hawaiian twilight

at a sunset hula

the final aloha

The final section, “Between the Lines,” contains the largest assortment of haibun (50 poems in total). It also takes the tone of the book from the mythological to the modern day; many of the haibun seem to be more autobiographical, with Cates offering observations from her life. However, Cates can still be the explorer, with tough, compelling, confrontational poems. The section begins with its title poem, which has an edgy tone reminiscent of the earlier sections:

Some days the walls close in. Your heart

drums beneath your skin, a distant

drumming, creeping through canopy and

liana vines. You wonder who is friend and

who is foe. Distanced from yourself you

cannot say, you do not know . . .

Other poems seem to come directly from Cates’s life. In “Stereotype,” she writes about teaching high school English and journalism on the Crow Indian Reservation. The reader also accompanies her as she walks a bike trail, surfs the web, waits in line at the DMV, and other everyday events. In these haibun, the prose becomes less experimental, more traditional— close, quirky observations made from behind Cates’ own telescopic lens. The poems focuses on the present moment, as we see in the simple haibun “Iowa”:

The voices in her head told her to drive out

to Oregon. So she did.

pig manure stench—

a farmer turns toward

the factory farm. . .

There are several of these minimalist haibun featuring the everyday. Another is “Fate”:

He's lied to me, so I can no longer trust

him. Still, the light is shining in his eyes.

after egg rolls

a dinner date and I

open fortune cookies

The collection ends with the haibun “The Happy Guy,” about a meeting in a store’s checkout aisle behind two young men. One of them declares his love for the middle-aged cashier and his friend declares, “He always embarrasses me.” Then the man declares his love for the haibun’s narrator, who responds in kind and leaves the store with her orange dreamsicles, seemingly uplifted by the episode—a feeling captured in the closing haiku:

a daisy's

yellow joy. . .

warbler trills

From Nazi Germany to declarations of love. . . The Golem & the Nazi takes the reader on a wide-ranging emotional journey. The book hammers out a place for itself and its author’s concerns amid the complexities of the past, the sensuality of the present, and the anxiety of a self deeply aware of its connection to a brutal, beautiful world.

About the Reviewer

Patricia Prime is co-editor of the NZ haiku journal, Kokako. She is the articles editor for contemporary haibun online and also a reviewer for Atlas Poetica, Takahe, and other journals.

Thank you, Patricia, for reviewing my collection!