Book Review:

Firefly Lanterns: Twelve Years in Kyoto

By Margaret Chula

Published by Shanti Arts Publishing

Brunswick, Maine, USA

2021, Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-951651-98-5

$24.94 USD

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Rich Youmans

In 1979, Margaret Chula and her husband, John Hall, returned to the United States after two years of peripatetic travel through Asia. They had experienced a swirl of different customs, cultures, and types of transport (from bemos to horses). Now they wanted to immerse themselves in another culture for an extended period of time. They chose Japan. As Chula writes in the introduction to her new book, Firefly Lanterns, in 1980 they arrived in Kyoto during the rainy season—the beginning of tsuyu, or “plum rain.” They found teaching jobs (during their time there she taught English and creative writing at two colleges), house-sat until they found a permanent home, and settled in for what became 12 years of acclimation and exploration in the “land of Wa.”

Firefly Lanterns offers glimpses into that time (along with accounts of a return trip five years after they left). Although the book includes many accounts of the “exotic” customs, landmarks, and people, it primarily records Chula’s personal experiences—those of a woman early in her life who, “unencumbered by children or jobs,” finds herself in an environment where she is the exotic one, with all the attendant wonder, surprise, and occasional embarrassment that engenders.

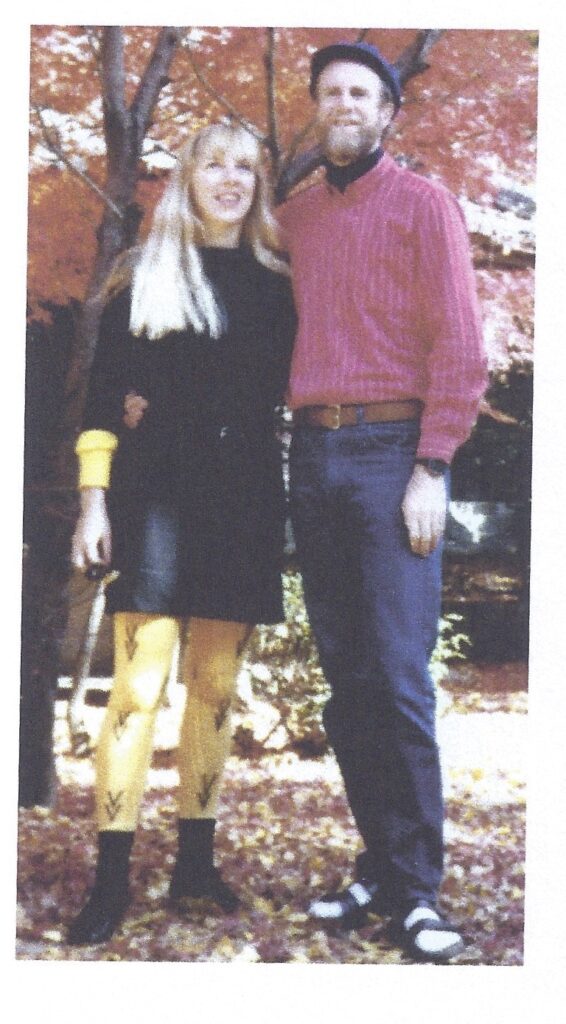

The 42 pieces in the book (all haibun except for two free-verse poems and one brief essay about a beloved teacher) have been assembled from among works published over the past few decades, and they cover a range of territory. Chula writes of encounters with Japan’s native flora (such as the plant that gives the book its title) and fauna (she is “bewitched” by visiting tanuki or “raccoon dogs”). She recounts culture clashes, including one in which the author tries to talk to her students about sexual harassment and molestation. She and her husband are gaijin—literally “outside people”—and as such they sometimes become objects of curiosity, whether in a public bath or in their garden (where Hall responds to prying eyes with a novel if somewhat salacious use of a large zucchini). Some of the pieces are enhanced by illustrations, including several photos taken by the couple during their stay.

Chula—a fine poet who has published several award-winning books of haiku, tanka, and haibun—recounts her experience with a graceful style, using spare, straightforward language. (A glossary at the back of the book helpfully translates and adds context to the various Japanese terms that appear throughout.) Here’s an excerpt from the title poem, “Firefly Lanterns (Hotaru Bukaro)”:

stars, stars’ reflections

mirrored in the paddy field

oh! the firefliesThey land on the grasses bordering the ride fields and on the hotaru bukuro, white bellflowers, that thrive in the damp soil. Tomoko plucks a bellflower for me and explains that hotaru means firefly and bukuro is sack. With our butterfly nets, we scoop the air and capture a net full of fireflies. Carefully we transfer them to the hotaru bukuro by opening the blossoms and inserting the fireflies into their petal-soft cage. Soon the flowers begin to take on the glow of the fireflies’ light. By the end of an hour, we have a handful of lanterns to guide our way home. Other fireflies are contained in jars. How many do we have? Fifty? One hundred? It’s impossible to count them with their lights flickering on and off, on and off.

Chula also explores some of Japan’s traditions and history, often through her visits to shrines, temples, and hermitages (of which there are many). At Hokyo-ji, a Buddhist temple in north Kyoto, she describes her participation in a “doll requiem,” where worn-out dolls are blessed and burned as a purification rite; she uses the opportunity to explore the role of ornamental dolls in Japanese girls’ lives. She uses a visit to Rakushisha—the hermitage of one of Basho’s most notable disciples, Mukai Kyorai—to remark on the lives of both poets. And a visit to the Zuishin Temple produces a reflection on the legend of Prince Fukakusa and his pursuit of the waka poet Ono no Komachi. This last haibun, “Well of Beauty,” won first place in the 2014 Genjuan haibun contest, and it offers a good example of how Chula enriches her observations with historical context, poetic reflection, and a powerful haiku.

Well of Beauty

It’s a dark place, this Well of Beauty, tucked into a corner of the Zuishin Temple grounds. Each morning the ninth-century waka poet, Ono no Komachi, would gaze at her reflection, then bathe her face in the healing waters from Cow Tail Mountain. Its distant flow tempered the chill—unlike her bitter heart. Entranced by her beauty, admirers would come, one after another, to her cottage gate begging for admittance. Her most famous suitor, Prince Fukakusa, is said to have courted her for ninety-eight days. On the ninety-ninth, the day before she promised to received him, he fell ill and died in a snowstorm.

The legend of Prince Fukakusa is reenacted every year on the last Sunday in March, with young maidens performing the Hanezu dance. “Hanezu” refers to the deep pink color of the plums blossoming on the temple grounds, a promise of spring.

I feel the darkness of Ono no Komachi’s heart as I descend the spiral of stones leading to the now-turbid water in her Well of Beauty—imagine leeches clinging to her milky white skin, ghost lovers entering the cavity of her heart.

from the mountain forest

I hear the cuckoo’s call

its blood-red tongue

In many cases, Chula uses the haiku and senryu effectively, as in the above examples. There are also instances where the poems read more as extensions of the prose. For example, the long haibun about the doll requiem, “A Gathering of Souls,” begins and ends with Chula’s attachment to one specific doll, Henry (a name she apparently gave to him, although it’s unclear why). Henry and his twin sister are among the dolls offered during the ceremony, and as soon as she spots him among the pile, Chula is entranced. After the ceremony, while staying behind to help load the dolls into boxes, she keeps an eye out for Henry. Ultimately she’s rewarded:

Then, as I delivered my last load, I spotted him. His delicate body had been jammed between a furry orange tiger and a teddy bear. But at least he was on top of the pile. His twin sister was nowhere to be seen. It was a sign, I told myself.

without a second thought

I tuck Henry inside

the folds of my cape

I wouldn’t really call these last three lines a haiku or a senryu; they’re more like a sentence pulled from the prose and divided into three lines for dramatic effect. In that sense it works, but for me such moments don’t match Chula at her best.

The book is divided into two sections: “Sunlight on Tatami—Kyoto 1980–1992,” which contains the majority of the pieces, and “The Pond Is Still There, but Smaller,” a dozen haibun about the couple’s return visits. “There’s a bittersweet sadness about returning to a place where your memories of twelve years are centered,” Chula notes in the latter section, and indeed, most of the haibun in “The Pond Is Still There” reflect on the ravages of time. Her old house “has caved in like a withered gourd,” and old friends have suffered losses that have left them like ghosts of who they once were. That is particularly true of Chula’s former ikebana teacher, Fumiko, whom all her students simply called Sensei. Upon her return, Chula finds that Sensei has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and the last several haibun in the book poignantly describe her teacher’s decline and Chula’s own moments of loss and letting go. Here is an except from “Visiting Sensei at the Alzheimer’s Home”:

When we arrive, Shinko leads us through the lobby and seats us in a reception room. We watch her take the arm of a hunched-over woman and speak to her gently. How kind she is. After five years of visiting her mother-in-law, she must know everyone here. But then, Shinko leads the woman from the lobby toward the couches where we are waiting.

hair shorn

waddling in diapers

my Sensei

The old folks are shuffling, wheel chairing, being helped into the dining room for lunch. They all look much worse than Sensei, completely spiritless. Yet I cannot be heartened by her sturdiness. I know it is only a matter of time until she becomes like them, just as I know that this will be the last time I see her.for the final photo

she smiles, I weep

no memory, memorynot knowing

what she has lost

—what is happy?holding her hand

into the dining room then

letting her goshe cranes her neck

to watch me leave

I wave and wave

and wave

Firefly Lanterns does have an overarching structure—the first section begins with the couple’s arrival in Kyoto and ends with their departure, and the final section captures the “bittersweet sadness” of knowing you can’t return to what was. However, as I was reading through it, there were several times I wished the book had a more cohesive flow. The pieces include not just Chula’s memories of her and John’s experiences in Japan and her resulting forays into Japanese culture and history, but an anecdote about the American poet Edith Shiffert and her husband; recollections of dreams tied to Japan; and a haibun about a chain letter that could have been written anywhere. There’s also some skewing of time: In the first section, a haibun about a visiting delegation of American haiku poets, hosted by Ishihara Sensei, took place not during the couple’s 12-year stay but in 1997 (according to a note that appeared with the haibun’s first publication in Modern Haiku).

That said, the book is obviously not meant to be a diary, a travelogue, or even a narrative memoir that proceeds chronologically. It’s more a miscellany of related experiences that provides glimpses into one woman’s early life as told by her older self, with the insight, knowledge, and understanding that age can bestow. As such, it’s a worthy addition to the bookshelves of not just those who enjoy haibun, but also those wanting to get insights into Japanese life and culture through the eyes of an “outsider.”

About the Reviewer

Rich Youmans lives on Cape Cod with his wife, Alice. His books include Shadow Lines (Katsura Press, 2000), a collection of linked haibun with Margaret Chula, and Head-On (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2018).

Beautiful Maggie—both you and your poetry!

Thanks so much, Dale.

Gorgeous work! I’ve learned so much 🙂