Book Review: at my doorstep

By Tapan Mozumdar

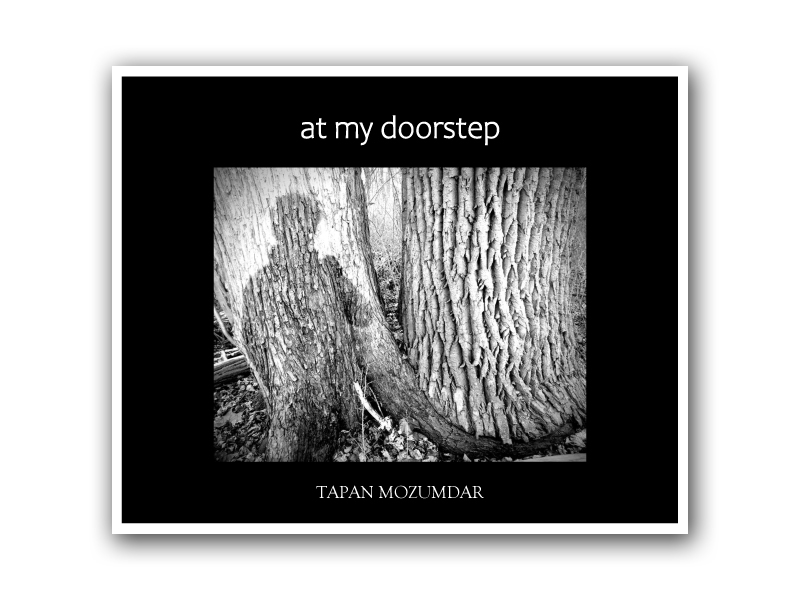

Cover & Interior Photos by Tom Clausen

Published by Yavanika Press

Bangalore, India

2021, PDF, 30 pp.

Price: Pay what you want (minimum $4)

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Bob Lucky

After reading the acknowledgments page of Tapan Mozumdar’s at my doorstep, I confess that I girded myself for an enthusiastic beginner’s haibun collection. Worst of all, it seemed to be one of those “Covid” collections that have mutated like viruses the last couple of years. I’m as sick of the pandemic as anyone, but I’m very tired of reading haiku and tanka and haibun about it. I understand write what you know, but I think it’s time for poets to let readers know they know something besides breathing into their masks. So, what to do?

I skimmed through and admired all of Tom Clausen’s black & white nature photographs, unpopulated by people but a couple containing evidence of them — a clock, a twig-fenced circle with some footprints, I think. What they had to do with any of Mozumdar’s urban-based haibun eluded me. Then I read a few of the haibun and it became apparent that Mozumdar can write. So, I skipped to the bio and confirmed my suspicions: He does write. Back to the beginning to start rereading I went.

I’ve read the chapbook a few of times now and like it better with each rereading. Other than the disconnect between the photos (which are excellent) and the haibun, my only complaint is that the link and shift in the haibun — title, content, and haiku/senryu — is occasionally obscure or heavy-handed. Take “Abracadabra,” for example.

Abracadabra

– Poets don‘t take bullets, or criticism, very well.

– I write poetry but I am not a poet.

– What‘s the difference? People are dying and you quote Eliot! April, May, June—all the months are going to be cruel. So? Your belly is full and internet bandwidth is paid, right?

– No offense, but we can quote poetry, and the better among us can write as well, when our sensitivities are hurt. What’s wrong with it?

– What‘s right with it? Will your anguish-laden metaphors get my brother-in-law an oxygen cylinder? Or, at least, a speedy reconciliation of his life insurance?

last local waiting for you to arrive

This is a piece in which the haibun magic escapes me. The dialogue is on the nose and the capping monoku, while a good one, is indeed a very stand-alone haiku.

However, Mozumdar writes some very nice haiku, and I’m drawn to his monoku, which often make excellent use of kire. Here’s an example where the possible kire give the reader something to ruminate on.

Failed Promises

Was there a tree here? Or an iron bench to cool off? Was there a puddle after an unwanted drizzle? Or some kind of undergrowth? I am sure that the place has changed, but I can’t put my finger on it. For one, the hundreds who cross this foot overbridge every hour are at home, if they are fortunate, or privileged. In the middle of the highway below, two brown puppies are prancing around their mother. At a distance, sitting on the railing, a jet black kite has its eyes fixed on the overflowing dustbin. A beggar family loiters on the bridge. They have always been there. The woman shakes her green enamelled mug at me. There is no clinking of coins today. The man is smoking a branded cigarette. The kids are pulling each other’s hair. “Anna, ek rupee, Anna! No? Stay well, Anna, live long!”

second wave nights aren’t the same dark

There are other things to consider in this haibun. The begging woman calls the narrator Anna, the term for an elder brother in Kannada (and Tamil). This linguistic assumption is based on my having read the bio; the author lives in Bengaluru. Some readers, a bit older than me perhaps, may have thought the woman was asking for an anna, 1/16 of a rupee in the old colonial coinage. Who knows? Knowing this linguistic tidbit helps me align the link and shift that ties the title and the prose and the haiku together. Now I sense that the elder brother has failed in his obligations, that the second wave of Covid has created a different darkness.

Unglossed words and phrases in world haibun in English create layers of meaning and hierarchies of readers, but one interpretation isn’t necessarily privileged over another.

Of Gods and Streetlights

On the main road, the modern temples of different gods are well-lit and worshipped. Its front porch is tiled and washed. We can’t find the Shiva lingam my wife is looking for. A priest says it is at the rear. Through wild grass and bushes, we find three unkempt hundred-year-old devalaya without any priests or doors. Built in memory of a Mudaliar patriarch, we find the lingam in the shadows cast by the granite jaalis on walls. No garlands, no lamps, no priests, just water dripping on it, drop by drop, from a suspended pot.

From the new complex, we hear chants of sandhya aarti. Here, I stand below the steps, guarding my wife’s slippers and worrying about an odd snake that may come to meet its lord. My wife lights the lamps she has brought and, after circumambulating the stone, holds it with closed eyes for a while. “They don’t allow anyone to touch the Gods on that side,” she says while stepping down, her face glowing with sweat under the streetlights.

pausing between our arguments summer breeze

Readers who know what a Shiva lingam is, what a devalaya is, who the Mudaliar are; who know a jaali when they see one and a sandhya aarti when they hear one will access or create a level of understanding different from those readers who don’t know (and from readers who bother to look the terms up). But any reader who understands the basics of worship is unlikely to miss the richness of the capping haiku. I find a slight but interesting difference between reading it pausing/between our arguments summer breeze and pausing between our arguments/summer breeze.

While there is an autobiographical component to many of the haibun, Mozumdar’s prose tends toward the observational and prose poetry. There’s very little memoir in the haibun. Two haibun — “Hers” and “Vaccinated” — are in third person. Two others — “Flash in Slow Motion” and “Falsetto” are in second person, although in both haibun “you” is a stand-in for “I.” This use of the second person serves no purpose and creates, as Rattle editor Timothy Green has noted1, a distance between the author/narrator and the reader. The authorial/narrative “I” is a clear and relatable voice in this collection.

Perhaps my favorite haibun is “Marginal.” I suspect that it is more embedded in the current Indian political situation than many non-Indian readers can appreciate. Or, I’m reading something into it, which is one of the pleasures and hazards of reading world haibun in English. Leaving the cultural context aside, it seems like a haibun an engineer such as Mozumdar might write.

Marginal

There are rules, and there are rulers. Rulers ensure straight lines. Lines define margins. Margin is the place you are put forever; the pristine white space inside is sanctum sanctorum. You know light doesn’t reach the inner quarters. You know that even then the non-evolving, non-mutating stone pieces shall be worshipped. Why? Because there are rules; rulers make them. Straight. Enclosed.

Along the road, outside the margins, the leader thinks he has briefly seen the gods and waves.

unreserved coach—

the moon from here

just the same

Pick up a copy of this chapbook. You won’t be disappointed.

References

- Green, Timothy. “Conversation between James Pennebaker and Timothy Green.” Rattle 74, vol 27: 4, 2021.

About the Reviewer

Bob Lucky is the author most recently of My Thology: Not Always True But Always Truth (Cyberwit, 2019) and the chapbook Conversation Starters in a Language No One Speaks (SurVision Books, 2018), which was a winner of the James Tate Poetry Prize in 2018. Lucky lives in Portugal, where he is working his way through all the regional cheeses and wines.

In this well-researched review of Tapan Mozumdar’s at my doorstep, Bob Lucky once again brings clarity with his straight-forward, critical voice tempered with subtle nuance (redundant?). His skill continues to reflect his review of student work those years ago, and his simplistic, depth-defying artistry through his own poetry.

I’m always left amazed.