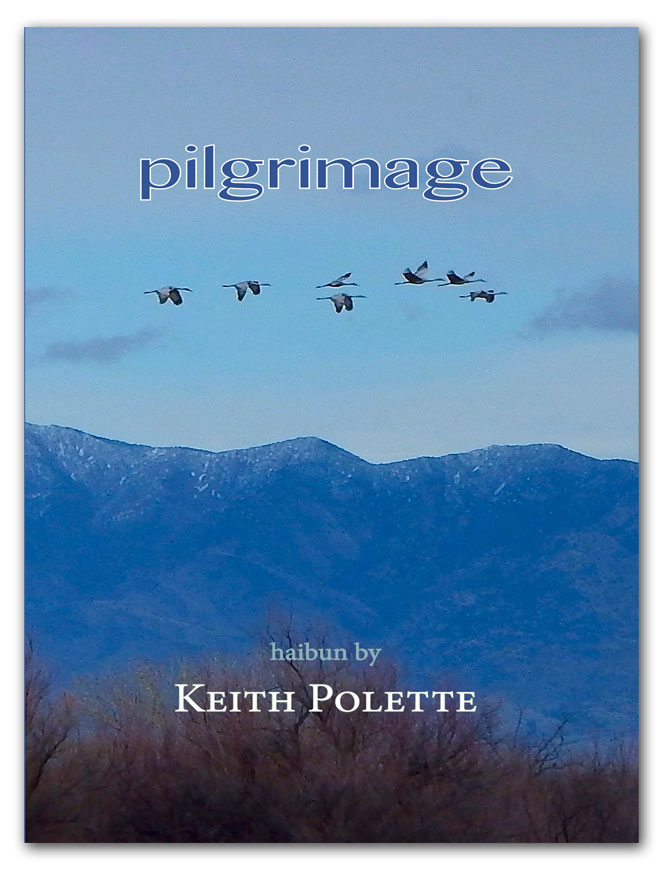

Book Review: pilgrimage

By Keith Polette

Published by Red Moon Press

Winchester, Virginia

2020, Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-947271-69-2

$15.00

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Rich Youmans

Keith Polette’s first book of haibun opens with an excerpt from a David Wagoner poem, “Lost”:

If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you,

You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest

Knows where you are. You must let if find you.

That directive to “stand still” emphasizes the need to be attentive and open, to let life’s nuances reveal themselves. That holds true especially in haikai, and in pilgrimage Polette amply displays his ability to pay attention and vividly share what he finds (or what finds him). In the book’s 42 haibun, the author pauses, shares his surroundings and experiences, and often reflects on his own place in the world. In one haibun, “Questions,” he says, “I began to wonder where I was, why I was, and even if I would be.” Such questions are the essence of a pilgrimage, which is by definition a journey in search of meaning about one’s self and one’s place in the universe. Polette’s collection can be read as episodes in his own search.

The first haibun, “From the Edge,” sets the tone and also illustrates Polette’s skill at descriptive, poetic writing.

Something calls to me from the edge of the desert, a fence of sagging guitar strings that no longer carries a tune, the scattered skulls of cows lowing to the wind, an arroyo mouthing a dry poem, stones rising out of the sand to sing of constellations that have never been named, a rusted truck turned-sphinx waiting for a lone traveler to question, a blue-tailed lizard, startled by the passing shadow of a hawk, that scurries onto the top of a rock, surveys the empty sky, and then rests like a monument to itself for the whole of an afternoon.

hands in prayer a butterfly brings its wings together

Polette transforms this desert landscape into something almost Dali-esque. The images pile like stones in a cairn, one on top of another—and then that final lift of the haiku, the juxtaposition of images that captures the spiritual side of what’s being described. It’s an excellent entry into what’s to come.

As it did in “From the Edge,” Polette’s prose often sings. I read the haibun sequentially, marking images and phrases that I particularly liked. By the time I was done, the book was littered with penciled checks, stars, and underlines. He has a particular skill in finding apt similes or metaphors that make his descriptions come alive. A few favorites:

“Today the tigers are inactive… lying in the shade like lumpy throw rugs.” (from “The Tiger”)

“…even standing still gave him the impression that his legs were made of river water, the currents pulling him downstream toward a destiny that would most likely be a waterfall.” (from “In Transit”)

“During winter, near the told of the world, the light is like an old man climbing the stairs.” (from “Alaskan Nights”)

Only occasionally does Polette’s facility become a little too exuberant, where a little paring/discipline could have strengthened a piece. In “Fishing,” for example, he begins,

Even though I think my father may have unconsciously wished it, he and I could never have been the subject of a Norman Rockwell painting—one where we are as content as warm socks just taken from the dryer—sitting in a wooden rowboat …

However, he soon turns to a different comparison (and sport), describing his father’s face first as being “wide and open as a catcher’s mitt” before shifting to a different position: “[H]e will then turn his face momentarily to the sky like a major league outfielder who has just leaped up to catch a long fly ball, keeping a home run from sailing over the wall.” Those three comparisons work nicely on their own, but they can bump into one another when placed together in such close proximity.

Although there’s no overt organizational structure to pilgrimage, you can see shared elements (a topic, an image, a season) that connect one haibun to the next. Most of the haibun seem to be derived from the author’s life in and around El Paso, Texas. They’re supplemented by episodes from hikes, family history, or just flights of fancy, which are especially evident when the prose turns a bit surrealistic. A few of Polette’s haibun would have fit well into a book by Franz Kafka, and I couldn’t help but wonder if the Bohemian writer had been an influence—Polette even refers to Kafka by name a couple of times. Here’s one in which he makes an appearance.

Kafka Calling

Kafka called, said, ‘visit Borges.’ ‘But you’re both dead,’ I said. ‘So what?’ he said, ‘go.’

Hitched a ride on a flight of crows angling south, landed in a maze of streets, everyone in masks, their eyes rolling like thunder, hailed a cab, felt like I was crawling inside an egg, passed by some buildings beginning to panic, came to a lurching stop, luckily I had a bag of raspberries, knocked on the door—smooth as the back of a violin—was greeted by Borges, or someone becoming Borges, who brought me into the library where, above a sleeping panther, books were singing on the shelves.

old insurance claims the vowels of fish

This fantastical trip to one of Kafka’s literary heirs, Jorge Luis Borges, left me a bit breathless, especially after that non-stop second paragraph with its symbols from Kafka’s most famous stories—the violin in “The Metamorphosis,” the panther in “The Escape Artist.” And the haiku (which I assume references Kafka’s early day-job at an insurance company) initially left me a bit disoriented—which, I guess, isn’t unusual in the world of Kafka. It’s one of the more extreme examples of Polette flexing his surrealistic muscles, but it’s not the only one. Polette often blends his acute eye for detail with a dash of reality-bending imagination, which (a tip of the hat to Kafka again) most often took the form of metamorphosis.

Throughout pilgrimage, I periodically came across haibun that featured the narrator taking on aspects of other entities (e.g., a tiger, a lizard, twice a bear), as if Polette were emphasizing the fine (or nonexistent) line that existed between us and other creatures. One of my favorites in this vein, “Hinge,” is not about a creature but a metal door hinge, which has echoes from that opening haibun.

Slip into a hinge that would be my move. Let someone else shrink into a key or pound and pummel with a hammer’s blunt head. I am happily a hinge… the hinge brims with many beings … like a butterfly’s wings, opens and closes between two presses of wood or metal and sings things that most ears, like dead oak or deaf dogs, never hear.

Polette relies exclusively on the most common format for haibun, a single block of prose followed by a haiku. (Personally, given his talent, I’d like to see what he could do if he varied his approach.) The majority of the haiku are three-liners, supplemented by a few monostitches here and there. Some complete or directly comment on the prose, as in “Questions,” where the prose ends with the “where/why/if” ponderings quoted earlier and the haiku references the text directly: “lingering questions/a wolf pack answers/the moon.” In a few pieces, the haiku shifts the context entirely. “The Pianist,” for example, describes an old woman literally disappearing into her rendition of “Claire de Lune,” while the haiku focuses on another setting of slow vanishing—”at dusk / I put the last of my cash / into the homeless woman’s cup”—and introduces an element of human compassion. Generally, though, the connections are more subtle: the haiku pick up on a word or phrase in the prose, or maybe one or more images or themes, as Polette searches for a new way to shed light on his subject. Here’s one in which light actually plays a role:

Galileo

Tonight, standing before the frosted window, I notice the moon, slender as an eyelash, fading in a slow descent. And I think about Galileo, not in his prime, when he witnessed the heavens whirling and darting like luminescent barn swallows cavorting in the center stage of his telescope, but later after he had been placed in lifelong house arrest. I picture him, stumbling in his blindness, lurching from chair to table, holding the rounded head of a spoon and feeling not curved metal, but the counter of a new planet, one that sounds like a single musical note.

whitewashed chapel the sun streaming through stained glass

Polette’s decision to use the radiance of sun-bright stained glass works on a couple of levels: It provides a strong counterpoint to Galileo’s blindness, and it effectively conveys the moment of discovery—as a reader, I feel it. I also like that the haiku is set in a chapel, given Galileo’s troubles with church authorities, as if the moment has erased all of the trials he experienced.

The collection ends with a haibun that picks up on that running theme of metamorphosis / transformation, of standing still to find and accept, Buddha-like, one’s place in this world. The only haibun written (like “Lost”) in the second person, it is appropriately titled “Invitation”—it’s not so much a conclusion as a stepping-off point for readers to continue the pilgrimage on their own. A fitting bookend, it echoes the opening haibun and, like it, begins on the edge of a desert:

If you stand at the edge of the desert and open your arms, every particle of sand will invite you to let go of the parts of you that you no longer need. Notice that rocks do not mourn their slow shift into sediment, nor do the arroyos curse the sky after their waters turn to dust, and the cactus wren does not grumble about its charred song. Stop and let yourself be like the rockcolored lizard, still as stone, and allow the long days of wind and breath to gradually wear you away.

It ends with a haiku that merges images of awakening and stillness into a single presence—the transformation complete.

river blossom the blue heron on one leg

Finishing this book, I was reminded of another line from Wagoner’s poem: “Wherever you are is called Here.” One of our finest haibun writers, Polette makes us all appreciate “Here” a little more.

About the Reviewer

Rich Youmans lives on Cape Cod with his wife, Alice. His books include Shadow Lines (Katsura Press, 2000), a collection of linked haibun with Margaret Chula, and Head-On (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2018).

What a spectacular review and invitation to immediately get in touch with Keith Polette

and buy this book.

Reading your review of “Pilgrimage,” this reader knows you have been accompanying Keith on his journey–you have absorbed what he has to offer and that makes for an objective and life-filled review. I appreciated hearing Keith’s voice and your response in such lucid prose. It felt like you were pulled into the haibun with a growing exuberance pulling me right behind you.

I read this review with as much pleasure as I do a good book.

Thank you.

Jo

Words fail in a comment, when the Reviewer and the Reviewee have become as one…

merging images

awakening and stillness

a single presence

—Rich Youmans, var. Review, ‘Invitation,’ in “Pilgrimage,” by Keith Polette, “Contemporary Haibun Online” cho 17.1 Apr. 2021, Gloria Rhea Grante haiku | 12 December 2021