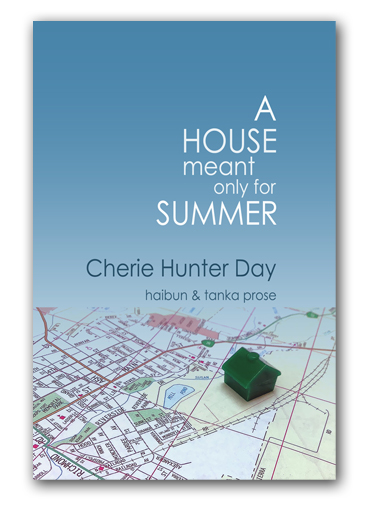

Book Review: A House Meant Only for Summer: Haibun & Tanka Prose

By Cherie Hunter Day

Red Moon Press

Winchester Virginia

2023, paperback, 80 pages

ISBN: 978-1-958408-34-6

$20 USD

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Rich Youmans

In her haibun and tanka prose, Cherie Hunter Day can sneak up on you. She knows how to frame a story—her work has appeared frequently in flash fiction journals such as Smokelong Quarterly, 100 Word Story, and Wigleaf, among others—and how to select the right details that add nuance and depth. Often, though, the true impact of her work is delayed, like a depth charge, occurring after the words have had time to settle within the reader.

This ability is on brilliant display throughout her new book, A House Meant Only for Summer, Day’s first book of haibun and tanka prose. While the collection is heavily weighted toward haibun (only 7 of the 57 total pieces are tanka prose), all the work shares Day’s subtle approach. The language occasionally soars (“Scrub jays toggle blue in sunlight. They fold that brilliance next to their bodies when they land” is a personal favorite). More often, she engages the reader with direct language, tightly honed sentences, and details that build, one on top of the other. The structures are simple—they primarily consist of a single paragraph and a poem—but all convey Day’s dedication to craft.

The book comprises three sections: “bits of eraser,” “at flight’s end,” and “the parentheses of night.” I’m always interested in how writers assemble work created over long periods (some of the book’s pieces date back more than 15 years); what threads, if any, can be found to tie everything together into a whole that’s more than the sum of its parts? Day, true to form, has found a structure that isn’t readily apparent and may even invite over-interpretation to make the connections. Maybe I’m guilty of the latter, but the more I read A House Meant Only for Summer, the more connections I saw (that depth charge again). The result is a book that turns Day’s disparate pieces into a larger reflection on what it means to be in this world and to find our true selves—to be “home.”

“Bits of eraser” begins with an old photo that conveys some hidden family tension, and it ends with a haiku focused on a therapy session; in between are a miscellany of episodes and meditations that seem to revolve around finding one’s place in the world. Some pieces focus on childhood hiding places or friends that don’t quite fit in; others on the innate traits of fish and fowl, or on the vagaries of memory: what we remember, what’s lost. All could tie in to the section’s theme—not just the erasure of memory, but also that constant desire to remove errant strokes and correct mistakes, to hone until the true nature of something (or oneself) is revealed. Here’s the haibun from which the section’s title is taken:

Today’s Math

Every school playground has a bully and here the toughest girl is in charge. She demands tribute and loyalty. Today she is testing for bravery. The skinny, quiet girl with glasses is a good candidate. She’ll fit easily through the basement window of the upper classmen’s dining hall. Phrase it as a dare and she’ll go willingly into the dark without complaint. She’ll even help replace the iron window grate behind her.

The recess bell rings. Legs like fleshy pistons pumping—all those shins disappear from view. It’s only an hour and a half until lunchtime. Meanwhile someone in the fourth grade is bound to figure out the solution to the math problem written on the blackboard.

pop quiz bits of eraser swept onto the floor

This haibun offers a good example of Day’s understated style. A straightforward story of children and our innate instinct to create hierarchies and fit in, the haibun ends with a twist. Is the quiet girl in glasses the one who figures out the problem, setting up the old brains vs. brawn comparison? Is the math problem representative of all challenges faced in navigating our relationships with others, to fit in while still remaining true to ourselves and allowing our strengths to shine? The haiku expands upon that idea, in a slant way: in those remnants of eraser, we see the efforts to correct all the mistakes and lapses in judgment when suddenly confronted with hard choices.

The second section focuses on the idea of “home”—in reality or memory— and the existential threats to it. Here, Days excavates the remnants of human life—a decades-old Kodachrome of a family get-together, an arrowhead from centuries past. She offers meditations on our ability to inhabit a space, and the way a place can turn on us and leave us “searching for new coordinates.” (Her haibun on the California wildfires are especially powerful.) But she does not focus solely on the human experience. She draws portraits of geese populating an urban park and refusing to be dislodged; of colonies of bumblebees and yellowjackets, and their efforts (successful and unsuccessful) to hold their ground. Here is the haibun from which the book’s title is drawn:

Sugar Work

The wind breaks its covenant with the bees inside the oak. Brisk gusts cause miscalculation in reception, muddle arrivals and departures. The sun has a flange too, but it’s factored in as part of the equation. There’s more static from the stars. You and I feel the effects of this decay firsthand. We live in this gap and struggle to find home. Behind the limb scar the hive has a pilot light that keeps the dance as shiny as an afternoon opera. Worker sisters with steady tongues and wings continue their sugar work in a house meant only for summer.

horizon's curve in the taste of nectar

Here, Day gets to the core of the section’s main theme—the “struggle to find home.” Moreover, it seems to be saying, any “home” we find is ultimately ephemeral: after the summer, what then? In many ways, this could be read as a meditation on mortality, but rather than despairing, the haiku opens up the reader to a beyond that is full of promise.

Day ends this section with several poems about her father’s death (some of the most heartfelt in the book, collapsing the distance she often assumes as narrator). They lead into the final section, which is really about … well, life, I guess. It begins with a scene from a laundromat and ends with laundry flapping from city clotheslines, ala Richard Wilbur’s “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World.” In between are 16 haibun and tanka prose arranged by season that take us from spring (or at least a spring-like setting) through winter, presenting scenes from relationships, hikes on country roads and up glaciers, meditations on love and family and dreams, the aftereffects of pain medication, and even a race of box turtles.

If it all sounds a bit chaotic (as life can be), what holds everything together is Day’s ability to tell stories and make us care. Here’s the first “laundry” poem, which also offers an example of her tanka prose:

At the Sunshine Wash and Dry

In the hubbub of Saturday afternoon, the usual customers file in and out. I come penitent with dingy whites. All the dryers are twirling their contents. The wheeled wire baskets holding piles of damp laundry stall in the aisles. Her loud greeting—the manager calls everybody “Baby.” One latecomer dashes in and receives her stern chastisement for leaving clothes in the dryer unattended. She points to the code of conduct clearly displayed as a list of dos and don’ts. An out-of-order sign perpetually hangs over the dollar slot on the change machine. She’ll redeem bills for quarters if you ask nicely. The coffee and day-old donut holes are free. From my bleached whites, fresh from the wash, she says she can tell that I’m a good wife. When the nearby church bells ring for 5 o’clock Mass, she shushes the customers with her index finger raised to her lips. The last rays of sunlight triumph over a patch of grey linoleum.

city bus passengers disembark and scatter a flock of pigeons the slap of their wings shaping Eden

There’s such a sense of promise and joy in this piece (honestly, how could it be any season other than spring?); as a reader, I’m there in that laundromat and don’t want to leave. After the Wash and Dry’s slice of life and its exuberance, Day’s versatility as a writer and poet is shown a few pages later with this short, somewhat cryptic meditation:

Our Bodies Stave Off the Darkness

Fireworks in this harbor seem like a destination but your inner voice doesn’t make it past the broken windowpane.

raindrops sheening the parentheses of night

Is Day saying here that during our brief time on Earth, between the mysteries of the times before we were born and after we die, our role here is to shine? Or, to pick up on the tanka of the earlier piece, to shape our own Eden? Maybe—Day leaves plenty of room for interpretation. What’s undoubtedly clear, though, is Day’s facility as a writer, her capacious mind, and a sophisticated worldview that, in the end, leaves the reader with, above all, hope.

At least, that’s the way I felt after finishing the book. The last piece, “Gravity in Winter,” depicts a scene of dresses, tees, scarves, and jeans flapping like prayer flags against the sky, and it ends with the sentence, “This time of day is a blue scarf that never tatters.” It’s a beautiful line, and it gains added meaning when read in the context of an earlier haibun, “Pantone Unveils Its Color of the Year,” and these sentences: “We are desperate for the calm that blue can provide. There’s a gravity to it that registers as comfort from a weighted blanket.” Those lines, in turn, echo the book’s epigraph, from Charles Simic: “Wanted: a needle swift enough to sew this poem into a blanket.” For A House Meant Only for Summer, Day found that needle.

About the Reviewer

Rich Youmans lives on Cape Cod with his wife, Alice. His books include All the Windows Lit (Snapshot Press, 2017) and Head-On (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2018). He is also the co-author, with Roberta Beary and Lew Watts, of Haibun: A Writer’s Guide (Ad Hoc Fiction, 2023).