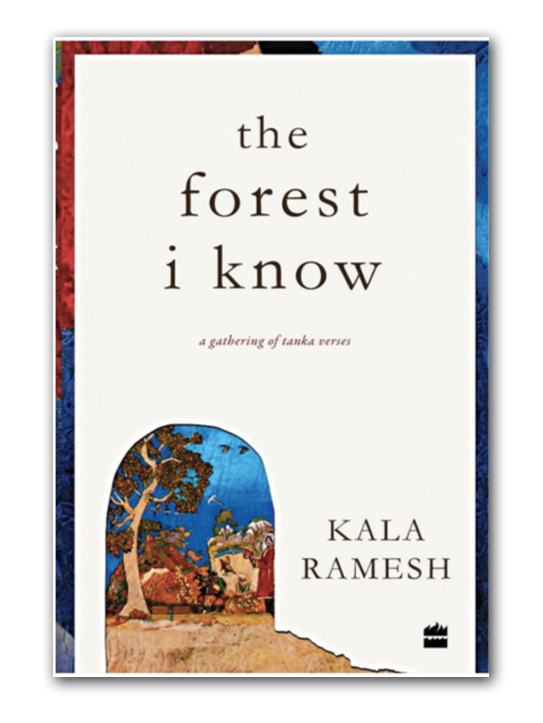

Book Review: The Forest I Know

By Kala Ramesh

Published by Harpers Collins Publishers

Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2021, Paperback, Kindle

P-ISBN: 978-93-5422-758-5

E-ISBN: 978-93-5422-790-5

$11.34, $7.99

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Tish Davis

With eloquence and brevity, Kala Ramesh introduces readers to The Forest I Know:

to: inward flowering...

still fresh in my mind

the song sparrow's twirl

sleepless

I hum a note or two

and set its wings to music

In this collection, which Kala Ramesh refers to as “a gathering of tanka verses,” readers walk alongside the poet and through a metaphorical forest nurtured from the same source—the poet’s pen, based on life experience. Observations, self-awareness, and recollections of the often-difficult journey on its paths are conveyed through individual tanka, tanka prose, tanka threads—which the poet refers to as tanka sutra—and an experimental tanka doha. This collection is by no mean a lamentation of the past, but an enlightenment of “self” unabashedly conveyed through poetry.

Ramesh titled the first of the book’s six sections “maya.” Her selection of verses reveals not only a forest that is real, but sometimes in need of illusion as a coping mechanism.

his anger turning on hers turning on him . . . their children are the ones who remember the s t r e t c h of an hour ** letting my anger off in layers until I'm naked. . . this water moon ** I find ways to cushion the wails of my mind. . . else the shock of thoughts would echo for days

I’m particularly fond of “Tangled Strands,” one of the five tanka prose in this section. Here expository prose blossoms as the last paragraph glides into the universality of her tanka.

Tangled Strands

My neighbour for a month now, she is nearly eighty years old. Straight and sprightly, her body belies her age. It is always her eyes that strike me. Lonely, with a faraway look, they seem to talk. I wonder if she was a dancer.

On the road a week back I met her face to face and tried to strike up a conversation. Her maid said she’s hard of hearing and generally doesn’t talk to strangers.

The row houses of our neighbourhood share the walls with neighbours. I’ve been hearing soft sobbing every night. Ashamed to admit it, the sound made a lullaby of sorts as I dozed off.

This morning there was a crowd around her gate, spilling over. Cars were parked on both sides of the road. My neighbour had died in her sleep. It was whispered that her only daughter had not visited for twenty-five years.

from a branch

silver threads stretch

into the unknown. . .

a search for keys to open

spaces that have no doors

In the second section, “backyard well,” Ramesh reflects on her childhood with multiple individual tanka and two tanka prose. Contrary to some of life’s difficulties that were expressed in “maya,” many of these selections recall the innocence of childhood.

as father prays circling the sacred basil we imitate placing our tiny feet against his wet footprints ** at twilight the forest I know by sight becomes of forest of sound . . . cicada summer

Ramesh seamlessly transitions to the next section, “pellets of desire,” briefly continuing that childhood innocence expressed in “backyard well” by way of her opening tanka prose, “This Woman Thing.” This tender piece—in which the narrator is twelve years old and unaware of menstruation—recollects that sudden spurt and warm feeling, and the guidance she received from her mother.

The poet’s “Chhand, The Inner Rhythm” is a tanka prose written in verse-envelope style (tanka, then paragraph of prose, then tanka)

Chhand

The Inner Rhythm.

searching for ways

to weave the loose ends

into my day—

sea waves rise as one

to color the sunsetFrom the path lost to twists and turns, our cows find their way back home. As a child, the twilight hour was special to me, because mother made it so. As skies darkened, she would insist on lighting the oil lamp first for Devi, before switching on the electric bulb in her kitchen. We would patiently wait and watch as she bent low to pour oil into the bronze lamp. She would then strike a match to touch it to the wick. What a surprise each time seeing her face glow in shades of gold.

with great flourish

the magician pulls out

two green parrots

giving wings to an old dream—

I float in my autumn bubble

Unlike the expository prose in “Tangled Strands,” a style which “fit” that piece, the prose style here is elevated. Ramesh uses imagery to describe the cows finding their way home after time lost on that path of twists and turns. The children also know the routine, gathering daily at twilight as their mother prepares to light the oil lamp for Devi.

Ramesh also guides the mind with color. In the opening tanka of “Chhand,” sea waves rise as one to color the sunset but, in the prose, both sky and the gathering space are dark. It is the simple strike of a small match and its placement against the wick in honor of Devi, that causes her mother’s face to glow in shades of gold.

In the closing tanka, both the magician and the green parrots are metaphors giving wings to an old dream. That child, now an adult poet, also finds her way back home.

Many of the poems in the next segment, “within and without,” elicited a strong sensory response.

the thrill

of first rains

in my hands

your hands

the first time I held them

However, I was totally caught off guard by the poet’s tanka prose “Thumri.” The poem opens as Ramesh enters the room of someone undefined, but familiar:

I enter her room. She’s singing with her eyes closed.

I’ve heard her; can recognize that voice even in deep sleep.

I didn’t connect with this tanka prose at first because in the first paragraph there are references to genres of Indian song styles that were unknown me.

Her ability to fuse meaningful shades to every song,

be it a thumri, a dadra, a kajri, or a bhajan.

Abhinyaha in those vocal cords.

However, it didn’t take long to look them up. (In other paragraphs some translation is provided in parenthesis.)

Then, during a full and uninterrupted reading, I heard the music, and was captivated by these words:

.

how effortless it seems.

It seems.I soon realize that beneath the simplicity of her gayaki (style) lies her deep respect for the perfect swara (note)

Tanka are sometimes referred to as “little songs,” and the sound of tanka prose, just like poetry in general, can be enhanced by poetic devices such as repetition, assonance, and consonance. For me, this tanka prose reflects the heart of Kala Ramesh’s poetry: her deep respect for that perfect note. This is a poem that deserves to be read out loud, especially the last paragraph and closing tanka;

Her limbs move. Her body sways. Her eyes dance. Her music weaves through the taal, joining the beat now, going off-beat again, teasing, just like the Ganga playing hide and seek with the Himalayas.

And now

she is no morethe night

all to myself. . .

I imagine

the unseen arc

of the crescent moon

Another favorite is “Azadi.” This tanka prose reflects on freedom and is conveyed through the personification of a fence.

Azadi

The diamond mesh fence has lived its life. Over many monsoons of neglect, it seems to have rusted and given way in places. With this sudden unwinding of once galvanized wires, one by one the rusted links unclasp, as if they know what it is to take off into the unknown and fill the sky like birds in flight, breathing azadi — the freedom to be.

a million

daydreams get buried

at sundown

both pariah and non-pariah

walk the fallen leaf pathif life’s so short

why are the nights

so long—

the day’s happenings

tossing and turning

In The Forest I Know, it is perhaps the tossing and turning and the private contemplative moments in poet’s life that opened her senses to the observations expressed in her poetry. Kala Ramesh’s ability to transform those moments, especially the difficult and painful ones, into thought-provoking poems with universal appeal is an accomplishment not to go unnoticed.

About the Reviewer

Tish Davis lives in Northern Ohio. Her tanka and related forms have appeared in numerous online and print publications. When she isn’t busy with work and grandchildren she enjoys exploring the local parks with her husband and three dogs.

I’m clean bowled, Tish.

What a magnificent review of my book and the 14 years of my poems you have analysed so beautifully.

I’m deeply, deeply touched by your generosity in how you have explained my poems and the depth with which you have revealed what I wanted to say.

The poems you have quoted are so in tune to the points you’ve made.

What can I say – except thank you, dear Tish and thank you to cho for this gift.

_()_

.

WoW!!

This is just fabulous! Taking us inside Kala’s forest is just magnanimous!!!

Wonderful review!! Thank you.

Thanks a lot, Lakshmi.

Deeply touched.

_()_

wonderful!

Thanks a ton, Corine.

_()_

Beautifully said Tish! I enjoyed the work of Kala Ramesh through your eyes:)

Thanks a ton, Corine.

_()_