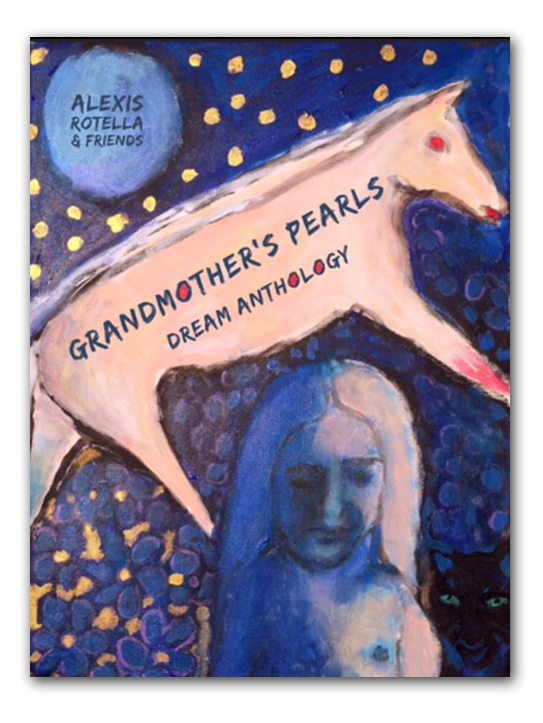

Book Review: Grandmother’s Pearls: An Anthology of Dream Poems

By Alexis Rotella & Friends

Published by Jade Mountain Press

Greensboro, North Carolina

2021, Paperback

ISBN: 979-8-529608-2-27

$24.80 on Amazon

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Rich Youmans

I don’t usually remember my dreams, and when I do it’s usually accompanied by a mix of fascination (“Wow, that’s bizarre”), confusion (“Huh?”), and curiosity (“What does that mean?”). After reading Alexis Rotella’s new anthology of dream poems, Grandmother’s Pearls, I found myself immersed in those same feelings. But if dreams can be disorienting, they can also be magical and enlightening, as they try to make sense of the world beyond the rational.

Rotella, who’s earned great acclaim for her haikai work over the past 40+ years, has had a long connection with the study of dreams. As she says in the anthology’s preface, in the 1980s she studied dream therapy with a Jungian analyst at the New School in Manhattan. Her immersion in the therapeutic techniques of German naturopath Peter Mandel (founder of Esogetic Colorpuncture, in which she’s certified) led her to realize the importance of remembering dreams. “I know when I don’t dream for a long while, I feel like something is missing,” she says.

In compiling Grandmother’s Pearls, Rotella says her main criterion was to present works “that capture the dreams themselves—I didn’t want dreamlike poems or poems about dreams. I tried to arrange the works into a rosary of dreamscapes.” Haibun dominate, but the collection also includes other forms, including haiku, tanka, tanka prose, even a cherita. As the byline “Alexis Rotella & Friends” implies, most are written by Rotella herself. (Of the book’s 84 assorted poems, more than half belong to her—a byproduct, no doubt, of the fact that she originally intended this to be a solo collection before deciding to invite others.)

Rotella has done a good job of melding in the work of those other poets (a full list of which is presented at the end of this review); tones shift but the overall voice of the anthology remains consistent. The pieces rarely mention the dream state itself; rather, they present each dreamscape as its own reality, faithfully recorded by the author. The collection begins with a haibun by Rotella:

Frequency of Love

A group of faceless female ancestors design a wedding gown from snowflakes. When the garment is finished, it lasts only a second, not long enough to take a photograph.

a spider spins its own constellations

I find something mesmerizing about this haibun—the way the spider filaments echo the fragile snowflakes and the gown’s intricate lace, and how the constellations and ancestors bring in the passing of eons, in counterpoint to the garment’s short-lived existence. It also provides a nice entry point for what’s to come: Just as the spider spins its own universe, so too do the dream worlds unfold, mixing forms, voices, and subject matter. Some dreams involve surreal threats—of being unable to find one’s way in a crowded city, of being attacked by wolves or buried under an avalanche. Some are especially fantastical, in a way only dreams can be. For example, in a haibun by the poet Billie Wilson, the dreamer transports from a high school classroom to the Arabian desert, where she writes a haiku in the sand and the words transform to gems. That idea of transformation occurs at several points throughout the book, including in this haibun by Kat Lehmann:

In the Now

I search for a day until I find one, then cut it in my hands, stroke its dawn long into evening. Shape the stone of it like a gift newly crumbled from a mountain of eons. A day brought by yesterday’s avalanche, on its way to becoming tomorrow’s sand.

midday sun

I become

a flower

A recurring theme is death—a result, Rotella says, of the collection being assembled during the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout the book, there are scenes in which the living prepare for the loss of loved ones, experience the afterlife, or converse with those who have recently departed—some of whom aren’t even aware yet of their demise, as in this haibun by Rotella.

Life Goes On

My mother’s funeral is about to begin, yet I find her picking bluebells along the path. What are you doing out here, you’re supposed to be in the chapel. You’re dead.

You mean those hymns they’re singing are for me?

Holding me still

a song from a bird

I’ll never see

As might be expected, the pandemic itself makes a few appearances—sometimes by name, sometimes obliquely. Barbara Kaufmann, a retired nurse, shows how, especially when COVID-19 was at its worst, the distance between reality and dream (or nightmare) was maddeningly thin.

Midnight Shift

Only this time, I’m wearing a gown, mask, gloves and a cap just like the ones we wore in the OR years ago. Except I’m not in the OR, but an isolation unit. It’s summer and I’m sweating—moisture flows between my breasts, down the inside of my legs, my back. The mask is soaked, breath sour. As soon as I finish with one patient’s care, another is rolled in. Then another. And another.

a so-called friend

holds my head

under water

Other pieces take a lighter approach, particularly those pieces that focus on the afterlife. In Rotella’s “It Happened so Fast,” the recently deceased narrator describes an encounter reminiscent of the movie “Heaven Can Wait“:

I arrive wearing my threadbare pajamas. I notice a small hole in the orange robe of the monk who greets me with a bow. He apologizes. Tells me someone made a mistake. It’s Mercury retrograde, after all. They were supposed to summon another Alexis, not me. But it’s too late now. The body I left cannot be revived. No sense grieving. What’s done is done. To compensate, they’ll put my name on a waiting list and when the right parties make love, they’ll push me off the cliff.

no curlicues in this waiting room

This piece makes me chuckle and the haiku is intriguing—but it also leaves me scratching my head (which isn’t unusual when it comes to dreams). Is the lack of curlicues a reference to the narrator’s inability to return to the same body/place/time? Or to the lack of ostentation in this afterlife—no trumpets blaring, just threadbare pajamas and a holey robe? It’s not really a haiku that can stand alone—take it out of this context, and it would simply be (to me, at least) a mysterious statement. It brings up a larger issue: at what point does a haiku—which traditionally has gained its power by allowing elements (whether stated or implied) to play off one another, producing some flash of insight or emotion—stop being a haiku? Rotella referenced her own view on this in a Rattlecast interview that she did with the editor of Rattle magazine, Timothy Green:

A lot of the haiku I write don’t have any juxtaposition, they’re almost like a statement, and I’ve been criticized for that many times. Most people do have juxtaposition in their haiku. Sometimes I do, but not all the time. I don’t think you should be sucked into any particular formula when you’re writing haiku.

Ignoring the fact that haiku practice in general has gone beyond simply relying on juxtaposition, I think it’s worth mentioning Rotella’s viewpoint on this only because there are several times throughout the book where (as in “Heaven Can Wait”) the poems do seem more like imagistic statements. That’s especially true when they go full-tilt surreal.

the bull manicures its toenails

—Alan Summers

an apple crawls back to its tree

—Paul David Mena

I feed my nightmare to a crocodile

—Alexis Rotella

(from the haibun

"Another New Moon, New York Dream")

Would these poems be called haiku, monoku, surrealistic fragments, something in between? However you view them, all stay with you and, as with the best surrealistic work, open up the mind to new possibilities. And in that sense, they all contribute to the book’s ultimate goal of presenting “a rosary of dreamscapes.”

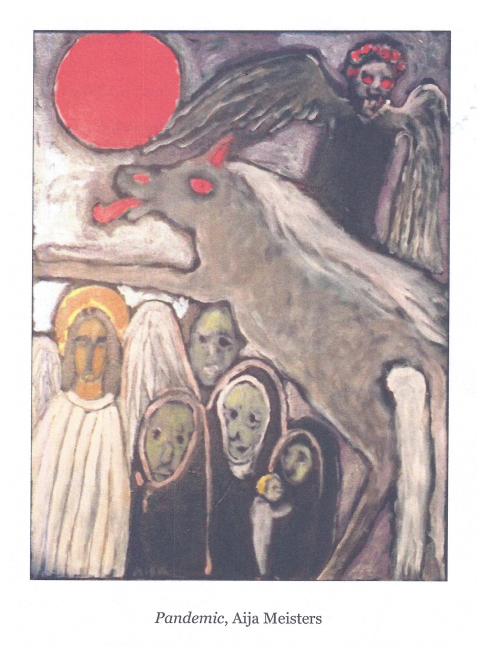

That “rosary” also includes a range of full-color artworks that punctuate the collection periodically. The works vary from drawings and painting to manipulated photos, with styles ranging from the primitive to the expressionistic. Although some are strategically situated (e.g., a painting by Aija Meisters, “Pandemic,” appears opposite Penny Harter’s “Pandemic Prayer”), they don’t illustrate but complement the prose and poetry, offering their own entries into the world of dreams.

Grandmother’s Pearls encourages us to see our own reality anew. “I know when I go through a period of intense dreaming, I feel so much more alive, as if connected to ancestors never met, with family and friends who’ve passed on, with spirits never before encountered,” Rotella writes in the introduction. After reading Grandmother’s Pearls, I know what she means. I may never look at my dreams in the same way again.

Note: The “& friends” in this book are:

Poets: Roberta Beary, Marjorie Buettner, Susan Burch, Jackie Chou, Margaret Chula, Terri L. French, Praniti Gulyani, Penny Harter, Barbara Kaufmann, Kat Lehmann, Carole MacRury, Marietta McGregor, Paul David Mena, Mark Meyer, Kala Ramesh, Paul Smith, Alan Summers, Billie Wilson, and Rotella’s husband, Robert Rotella.

Artists: Feliz Ak, Julia Badakhshan, Melissa D. Johnston, Aija Meisters, Cheryl Parris, Francisco Almendros Picazo, and Peter Wilkin.

About the Reviewer

Rich Youmans lives on Cape Cod with his wife, Alice. His books include Shadow Lines (Katsura Press, 2000), a collection of linked haibun with Margaret Chula, and Head-On (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2018).

A colleague of mine, after reading the review, exclaimed, “I never expected a male to write such a review, my gender bias.” I told her many men who write in Japanese poetry forms are very much in touch with their inner moon.