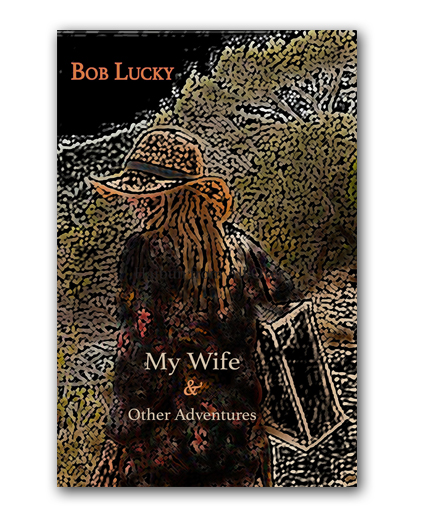

Book Review: My Wife & Other Adventures

By Bob Lucky

Red Moon Press

Winchester, Virginia

2024, paperback, 112 pages

ISBN: 978-1-958408-45-2

$20 USD

Ordering Information

Reviewed by Rich Youmans

Bob Lucky’s latest book is structured as something of a travelogue: a series of haibun set in various places around the world (specifically Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe) where Lucky has lived or visited. And, this being Bob Lucky, the trips go into realms beyond geography.

Yes, readers can accompany him on his visits to various temples and pagodas in China and Nepal, or to in a Jewish neighborhood in Istanbul during Ramazan, where men “sit at cafes and quietly finger ashtrays and prayer beads.” They can stand with him at sunset on a guesthouse balcony in India, staring into a valley where prayer flags “tongue their hopes and pleas into the rising darkness,” or sit beside him on a death-defying taxi ride in Bahrain. But Bob Lucky is not your typical tour guide. His haibun have a style all their own, exhibiting a dry humor and an appreciation for the absurd, with haiku that can offer subtle and sometimes surprising resonances. After reading him, I often find myself smiling (if not laughing out loud) and better appreciating what it is to be human.

As longtime readers know, Lucky served as editor of cho from 2016 to 2020, and he has also authored several previous collections, including Conversation Starters in a Language No One Speaks (which won the 2018 James Tate Poetry Prize) and Ethiopian Time (which earned Honorable Mention in the 2014 Touchstone Awards). He also, in his day job, taught International Baccalaureate classes until his retirement in 2020. His profession sent him abroad for decades, locating in such countries as Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia, far from his U.S. roots in Wisconsin. “I haven’t lived in my ‘home’ country in years,” he said in a 2015 interview. “I’m like the so-called professional stranger.”

In My Wife & Other Adventures, readers get a glimpse into some of his journeys. (Despite the title, his wife, Lisa, appears in only a handful of pieces. But as the book’s dedication to her says, she’s “there even when she isn’t,” one of the mainstays in Lucky’s peripatetic life.) The book comprises three sections. The first, “The World in Bits and Pieces,” contains 40 haibun chronicling visits to 16 locales. Some recount episodes from his teaching career. Others take the reader along on what seem to be vacation trips, such as this one to a temple in Cambodia, where the unexpected takes center stage.

Angkor Wat

I’ve come prepared, armed with historical data and guidebooks, a fair knowledge of Hindu mythology. The camera is charged. All the items on the checklist have been ticked: sun block, mosquito repellent, hat, umbrella, bottle of water. I’m overwhelmed, however, by butterflies, their colors: orange, rust, black, brown, yellow, white, a pale lime.

cloudy sunset

the tour leader

waves her flag

In so many of his travels, Lucky allows his “adventures” to find him. (As a dinner companion notes, quoting the explorer Roald Amundsen, “Adventure is just bad planning,” and one gets the feeling that Lucky relishes the unplanned). He also has a gift for finding the memorable in the mundane. Many of his haibun recount experiences that could have happened anywhere. That’s especially true of those pieces set in Portugal, where Lucky and his wife now live. We readers come along on their visit to a public market, meet some of the neighbors, and listen in as Lucky’s wife practices Portuguese by repeating phrases over and over. (“It sounds like she’s had a stroke,” he says, “but it’s just a lesson on making plurals.”) Even outside their home city, the adventures can arise from the most commonplace circumstances, without a temple, castle, or landmark in sight. A visit to a sidewalk bookseller in India. Lunch with a colleague in Thailand. A session with his physician in China, a Dr. Livingstone (really). In this latter haibun, Lucky shows off his signature wit and humor in four paragraphs that are really four incredibly long sentences capped by haiku. For example:

I am wishing my wife were here because she knows everything that is wrong with me, like the sneezing I always forget to mention, as Dr. Livingstone and I gossip a bit about mutual acquaintances and he gets down to business taking my pulse and checking out my tongue and asking questions about my digestion and appetite and cough and have I been following his dietary recommendations, and I tell him that China makes me sick, and he laughs because we both know the air is horrible and we might as well take up a three-pack-a-day habit, and I’ve been coughing for two years, which he already knows, but my appetite is good and every time I eat fried food I think of what he’s told me, and then I remember a recent foot massage I had and tell him about how the masseuse looked at my big toe on my left foot and said I wasn’t sleeping well, and he just gives me this funny smile and says, “they always say that about your digestion.”

overcast skies

artificial sunflowers

turned to the window

The book’s second section, “I’ll Always Have Trieste,” is a sequence of 21 haibun about Lucky’s visit to the Italian seaport that has attracted the likes of James Joyce, Rainier Maria Rilke, and Italo Sveno. All are mentioned, as are other notable writers, musicians, politicians, and philosophers—from Oscar Wilde and Gertrude Stein to César Aira, Lydia Davis, and Amy Hempel—whose quotes are used as epigraphs throughout. The entire sequence, in fact, is prefaced with an epigraph from the Argentine-French writer Julio Cortazar: “In quoting others, we cite ourselves.” Perhaps Lucky, who went alone to Trieste, meant to present all these notables as his traveling companions? Maybe it’s another way of saying, “Wherever you go, and whoever you go with, there you are”? It could also have been just a fun exercise. Whatever the intent, the quotes work well to introduce each haibun and set a tone. (The sequence is followed by an “addendum” in which additional quotes are collected and capped by a haiku to create something of a found haibun.)

I found Lucky to be at his most adventurous in this sequence. It’s not that his writing style differs in any way from what appeared in the previous section (although it does contain the first erasure haiku of his that I’ve seen). Instead, he employs a reverse structure for the sequence that begins at the end of the two-week trip, when he’s departing Trieste in a hard rain that’s turned his walking shoes into “soleless sponges” (pun no doubt intended), and ends on the day of his arrival in the seaport city. In between are a series of vignettes that describe a trip that begins well, with plenty of local delicacies (a few times Lucky had my mouth watering) but soon begins to lose its fizz. As the days go on, more grumblings appear—disappointments, frustrations, the sense of being a stranger in a strange land:

I wake up lonely. I takes time to get used to being alone no matter how much you like it. — from “The Plan”

I love museums but don’t think big museums were designed with people in mind.— from “One Collection Leads to Another”

I listen carefully to this group of men, but the only word, a name, that I understand, and it pops up with surprising frequency, is Barry White—from “Flaneur for a Day”

By sequencing the haibun in reverse order, Lucky not only presents the trip for what it now is—a look back—but also instills more poignancy by ending the sequence with that initial rush of expectation and promise, when (as a quote from English author Geoff Dyer notes) “[h]owever tired you are, however shattered by the flight, you are impatient to get out and sample the streets, the life, the action.”

Perhaps inspired by those he quotes, Lucky is also at his most philosophical and self-reflective in this section. By the trip’s end, Lucky says he’s made himself at home in Trieste—and “whenever I have a chance to leave home, I go.” It’s one of those head-snapping sentences that can leave the reader wondering what exactly this concept of “home” means for a man who has called himself a “professional stranger.” What does propel him? It’s a fair question, and one that Lucky seems to answer in “Dream On,” which begins with this quote from the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek:

Happiness was never important. The problem is that we don’t know what we really want. What makes us happy is not to get what we want. But to dream about it.

Lucky echoes that in the haibun:

There’s a segment of tourism waiting to be exploited: real estate tours for tourists. I see it everywhere—tourists, often couples, lingering in front of a real estate office, perusing the listings in the window, calculating the possibilities, dreaming of another life in another country, a small apartment in the city, a farm. I could live in Trieste.

window shopping

my reflection

checks me out

It’s all about the dream—at the end of which, there you are again.

Lucky returns to the idea of “home” in the book’s final section, “Envoi.” It contains a single poem that’s a call to exploration—not necessarily across geographical distances, but into life’s mysteries and wonders, through which we might actually find ourselves.

Home

Some people insist they’ve been there before, but they can’t remember where it is. It’s not on any map. No cartographer is willing to stake a claim, and publishers bicker over what color it should be. In a letter to the Society of Explorers, I suggest that all maps be blank so that everyone can be an explorer. I’m still waiting for a reply.

bus strike

the many ways

to my front door

It’s a journey beyond maps, but not beyond haibun. At least, not in the hands of someone as skilled as Bob Lucky. I’ll take him for a tour guide anytime.

About the Reviewer

Rich Youmans lives on Cape Cod with his wife, Alice. He published his first haibun in 1994 and, over 30 years later, is still at it. He recently co-authored, with Roberta Beary and Lew Watts, Haibun: A Writer’s Guide (Ad Hoc Fiction, 2023), which received the Prose Book Award in the Haiku Society of America’s 2024 Merit Book Awards.

Great review of a great book. Bob Lucky always delivers!